Category: Politics

Monday, Jan 27, 2020 | Art, Big Thoughts, Cartoons, Drawing, Manifest, Politics, Spirit, Stand, Word of the Year |

Choice is power. But the illusion of choice renders us vulnerable to exploitation. I woke from this morning’s 20-minute nap with this thought clear in my mind.

I’d been reading an article in The New York Times (a very long-read, as this manifesto before you threatens to be), called “You Are Now Remotely Controlled.” Upon waking, I sat down with my notebook and began to write. “I’m having an important idea,” I told my youngest, home from school today because his teachers are striking in support of strong public education. “When will you be done with your idea?” he asked, at last. He wanted me to pour him a bowl of cereal. “It’s turning into a very big idea,” I said. He poured his own bowl of cereal.

I want to use this reflection to pull together a number of disparate thoughts / observations / concerns about choice, autonomy, responsibility and shame. I want to reflect on how the illusion of choice shames us into believing that we are willing participants in our own exploitation, that we’ve willingly consented to give away our private lives, and that we deserve what we get. We might even believe that we prefer it this way. Anyone with a car can drive Uber or Skip the Dishes to earn a bit of extra cash; anyone with a room can rent it out at their convenience; anyone with an internet connection can publish a blog for free; anyone with a cellphone can become an “influencer.”

But it’s this illusion of choice, this illusion of independence and personal autonomy, that makes us vulnerable. It is only when we know we are oppressed that we can fight back. If we are kept in a state of confused distraction, if we feel shame about our personal choices (which may in fact be “choices”), we will remain disorganized, overwhelmed, stressed out, and isolated, even while believing ourselves to be ever more connected. Sure, we’re connected — but to what, and by whom?

I can’t stop thinking about something Trump said while still a candidate for the presidency: “I love the uneducated.” I think he instinctively understands the moment in which we’re living, which makes him especially dangerous. We think he’s joking when we says things like this, but he’s actually incredibly transparent: he’s stating his game plan (and it’s not just his). As citizens of democratic countries, we not only want to imagine ourselves free, our identity relies on it. Paradoxically, this makes us vulnerable to manipulation too; when identity is at stake, recognition of a different version of reality can be too painful to accept. The less we know, the less equipped we are to understand and interpret our triggers, which are attached to our pain, let alone to distinguish between facts and “fake news.”

It’s my observation that the gig economy is a function of this moment in time, too. We’ve been sold the idea that contract employees are willingly trading security for independence. But the gig economy only makes sense if those employed by contract can earn enough to live at a similar standard to those employed in traditional jobs. And it’s clear we can’t. Also clear that the gig economy puts pressure on the individual to support themselves in ways that go beyond their capacity as individuals to fulfill — to negotiate higher wages, save for retirement, etc. Further, the gig economy has the effect of eroding traditional jobs — with labour so cheap, and labourers so plentiful, who can afford tenured professors, for example?

What “You Are Now Remotely Controlled” focuses on, though, is the power that data mining — which feeds artificial intelligence — gives to private corporations, whose interests fundamentally put them at odds with our interests, with the public good. Instead, we become consumers to be activated by “remote control.” Our phones are always with us. (Mine is plugged in beside me right now, ringer on.) We can’t imagine life without this device that only recently entered our lives — I didn’t carry a cellphone on my person till around 2010, yet I went into full-on panic when briefly separated from my phone due to a mix-up this past weekend. What would entertain me while I did chores? And what if someone needed to reach me? I was like a smoker separated from her pack of cigarettes.

Okay, so I’m addicted to my phone. I confess it. Aren’t most of us? Despite surviving the majority of my life without it, I seem convinced that my well-being depends on it. Yet it is this device, according to “You Are Now Remotely Controlled,” that makes it so easy for me to be monitored and manipulated — it is an important tool, among many other tools in the “internet of things” that is turning us into robots.

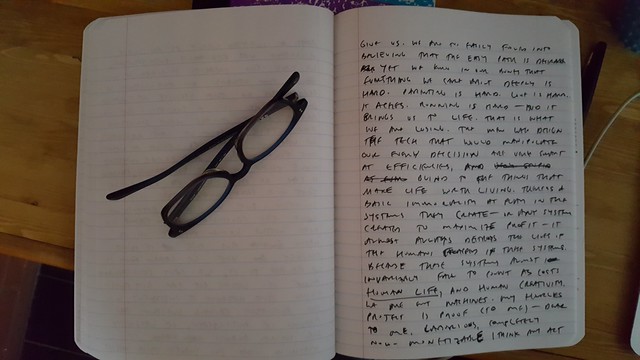

I am writing the first draft of this reflection by hand, in my notebook. The act of writing by hand becomes, in our era, an act of rebellion against the norm. A notebook cannot be surveilled. It is not connected to anything but itself. (Not to mention that my handwriting is virtually illegible, even to me.)

Surveillance capitalism traffics in prediction. The better a corporation is at predicting what we want / how we feel, the better it is at telling us what we want by understanding what we’re feeling. We are not, in fact, private autonomous individuals making multiple choices independently every day, we are highly predictable creatures with our inner lives, habits, routines and decisions being carefully monitored and collected digitally.

I’d like to connect the NYT article to a program that aired on the CBC’s Ideas on Friday evening, which was so compelling that I didn’t turn it off, even after I’d finished the dishes. It was part 2 in a series called “Why journalist Emily Bell is calling for a civic media manifesto.” Bell observes that it is legitimately becoming more difficult for us to find trustworthy news sources, especially at the local level. (Note that the two sources I’ve used for this post are The New York Times, which is probably the biggest independent newspaper in the world; and CBC radio, a public broadcaster funded by the Canadian government.) As anyone who works in journalism knows, the industry has suffered massive job losses and cuts over the past decade; we also know that bloggers are no replacement. A journalist without independence (or without adequate independent funding) is not free to do their job. “Influencers” are an example of personal journalism that is manipulated, easily and cheaply, by corporate interests. Why? Because an individual is personally vulnerable. An individual lives on a knife’s edge. She has children to feed, her reputation to protect. Freelancers need to get hired again, and again, and again.

This is what the gig economy thrives on. It’s the illusion of choice that I flagged way back when, at the beginning of this very very long essay.

An individual will sacrifice a great deal in order to feed her children, keep a roof over her head, and ensure she’ll get hired again. And she’s exhausted. There’s only one of her. How can she afford to anger the rich and powerful? When I worked as a sessional lecturer, I talked to a department chair about the insecurity built into the system: they tried to explain that I was fortunate to be given courses for two consecutive terms. That’s eight months of work. The standard for contract lecturers, in my experience, is to be given a contract for a single term (four months of work). And then you have to reapply, or perhaps, if you’re lucky, you’ll be offered a contract again, seemingly out of the blue. There is no stability. I was trying to explain, in return, that this made it very difficult to plan ahead. And they explained that the budgeting system made it impossible for them to make better offers. As I sat in their office, I thought, We are two human beings trapped in an inhumane system. How many people at the university were employed as contract lecturers, I asked them? And they said there was no data available on that. They suggested I could find the data myself, contact fellow adjuncts and contract lecturers and try to organize, to protest. I was flabbergasted. I was one person. I had limited resources, was already overstretched and underpaid. I was exhausted.

The NYT article suggests that protection for individuals requires governments to pass stronger laws, supported by the slow but certain democratic impulses of their citizens; this may be the solution. But is it too late? As Emily Bell points out, large data-mining corporations now possess more information than any single government. What would regulation look like? Who would enforce it? Who has the power? I fear totalitarianism by stealth. I fear all that we are accepting without question.

“Who will write the music, and who will dance?” writes the article’s author, Shoshanna Zuboff.

I can think of a number of policy changes that would help. A living minimum wage would go some distance toward reducing inequality. Strong public education with well-paid teachers is foundational, too. (“I love the uneducated.”)

But in Shoshanna Zuboff’s words I hear something that’s already within us — it’s our capacity for creativity, our capacity to write the music, real music, not computer generated. Algorithms are inherently boring. They are designed to predict the future; in other words, they’re predicated on predictability. It’s why I find Amazon’s suggestions for books I might like so boring — what I want is a human being who loves reading, in a bookstore, handing me a selection that’s a bit off the wall and unexpected, something I wouldn’t have chosen for myself. Human beings have the capacity to surprise ourselves and others. In surprise is delight. An algorithm offers, instead, a solution. But our brains don’t necessarily want solutions and efficiencies — we want absurdity, we want to be able to laugh and to weep at what we intuitively understand is not fixable. We crave mystery, though it can be difficult to recognize that — a page-turner, I would argue, takes us toward a solution, but we read it because we love the process of getting there.

Here’s a good example: Little Women is a beloved and much-read book not because of its tacked-on happy ending, but because of its imperfections — because we know the happy ending feels tacked-on (as Greta Gerwig’s film’s version brilliantly subverts). But if Jo and Laurie had married, I doubt Little Women would still be read, and relevant, today. We love Little Women for its complexity, for the messy emotions it evokes in us, and because it reminds us of our own imperfect lives. When I was a kid, I read it over and over again, and I couldn’t stop thinking about it — how it could have turned out differently for Jo, how unfair things were, how it lit in me a longing for a different ending, and yet how I had to accept it, nevertheless. This is the pleasure, the delight of the “wrong” solution, the solution unknown to the algorithm.

Something else. When we can buy anything and receive it instantly, we are denying ourselves another pleasure, that of anticipation, of weighing our desires against our needs, of imagining what the wanted thing might give us. We have been lulled into believing that the easy path is desirable. Yet we know in our bones that everything we care about deeply is hard. Parenting is hard. Love is hard. It aches. But it brings us to life. That is what we are losing. You know that feeling when you walk into a room and everyone is staring at their screens? And they glance up and their eyes are blank and they look numb? The men who design the tech that would manipulate our every decision are very smart at efficiencies, and at making us want more and more of whatever is being sold; but what makes life worth living? There’s a basic immorality at play in the systems they create — or any system created to maximize profit: an indifference to what’s being destroyed. And what’s being destroyed is the humanity of the humans lured into and trapped in these systems.

I gave up being a contract lecturer not exactly because I didn’t like teaching, but because I despised the system, and could not support it, if I could afford to choose otherwise. So I calculated what we could afford, and I chose otherwise. But the truth is that I didn’t really want to be a tenured professor either; I could see that their roles were untenably uncomfortable too, in many ways. It makes me wonder what to wish for.

The problem with systems designed for maximum efficiency is that these systems almost invariably fail to count some losses as actual costs; the losses that count are the ones found on a ledger. The loss of an individual’s security is not counted as a cost. Nor is the loss of an individual’s creative life. Nor the loss of pleasure, relationships and community-building when an individual is stretched to the limit just to survive, or when an individual has as colleagues other individuals who are treated as second-class.

We are not machines. We can’t live like we are. We won’t thrive. Here’s my own personal proof: I’m close to completing a project that I started a year ago in February, which I call “The Hourlies.” Each month, I’ve taken a 24-hour period and drawn a cartoon depicting each waking hour. It’s laborious, time-consuming, very dear to me, and completely non-monetizable. It’s also an enormous accomplishment in which I take great pride.

Drawing a cartoon is an act of creative rebellion. And each act of creative rebellion is an antidote to the paranoia, despair and fear that we’re being fed daily.

You know, Trump is half-right in his paranoia and fears — we are being monitored and many news sources are untrustworthy; he’s tapped into real fears and that gives his message currency and power. It’s just that he’s also the logical conclusion of what happens when we let paranoia, disinformation, ignorance, gossip, fear, greed and self-interest become our guiding principles. So let’s not do that, even though we could, even though we’re being pushed to. If we become like Trump’s example, we will live only on the surface of our lives, sating our base desires, but cold to the best of ourselves, to our openness, generosity, curiosity, and our imaginations, where images live.

Images can be used to manipulate us, too, of course; Trump knows how to draw a crude portrait that calls out our basest emotional responses — disgust, envy, greed, rage and fear. But images nevertheless remain my personal source of hope.

I think we can fight images with images.

Images can become stories, poems, drawings, songs. Images can be made into something that helps us see and know that we are human, we are alive, we are not machines. Visit with your own personal imagine. Let the joy of surprise and creation pull you away from your devices and screens, at least for a little while, every day. Call it your own personal rebellion against the surveillance economy. Get a cheap composition notebook and a black pen, and let yourself be led.

Maybe our creativity will disrupt the cruelty of efficiencies. Maybe policy will follow.

Thank you for reading all the way to the bottom.

xo, Carrie

Saturday, Jan 11, 2020 | Art, Confessions, Current events, Death, Mothering, Peace, Politics, Spirit, Writing |

This is a gift from a friend, from Iran. She gave it to me on Wednesday evening. While I had the words to thank her for the gift, I felt tongue-tied and incapable of properly expressing my grief and horror for what is happening in her homeland. I have felt submerged and helpless by the news of the plane shot down near Tehran, and all those lives senselessly gone; 138 people on that plane were coming to Canada, some were citizens, others were permanent residents or students. Young and old. The wealth of talent they had brought and were bringing to Canada speaks to how fortunate we are, as Canadians, to be blessed by the knowledge and skills and gifts of people from around the world. I hope we live up to expectations, though I know for sure that’s not always true. I wish we would be the country we aspire to be, and that we often tell ourselves we are.

This coming week, my life fills up again with extra activities, beyond writing and parenting. Soccer starts on Monday, with practices and exhibition games to plan; and The X Page workshop starts on Wednesday, twelve weeks of adventure and potential and hopes and challenge, leading to a performance on April 3. Click here for more information (you can already buy tickets!).

Meanwhile, I’ve been writing and writing. Let me tell you what that feels like: BLISS.

The release into another way of being feels so effortless while inside of this state. This is bliss, I’ve said almost every day this week, by which I mean transcendence, by which I mean, entrance into this other realm of existence where I am open to mystery, filled with wonder and delight, delighting in not-knowing, as if on a perpetual adventure and also feeling deeply powerful — feeling certain that it is a worthy undertaking to attempt to bring forth and make manifest and visible the spiritual, the otherwise unknowable and unknown world, through stories, through fiction.

How to connect that world to this one? That way of being and seeing and existing to this one? I don’t know. How to make sense of this escape when all around me is need, responsibility, confusion, and how can I live both there and here?

I wrote the two paragraphs above at my writing group, yesterday, and after I’d read the reflection aloud, one of my friends said: This should be our manifesto. We spend a lot of time talking, in the group, about why we write, what matters, what draws us to this discipline. How can we live both there and here?

One last curiosity: this morning, I opened a notebook that I thought was blank, and discovered several entries, scribbled in pen, dated not long after the birth of my first child. More than seventeen years ago. I was in my twenties. I was pregnant with my second child. Here’s something I wrote, in between describing teething, exhaustion, and anxiety dreams: “have felt mildly depressed after getting no writing time all week, no breaks from mothering & cleaning & cooking, etc. i need it, it feeds me. i think it is this other world for me, an escape, a place where things make sense and have significance or can be made to seem so.”

What a remarkable reminder: I’ve needed it, it’s been feeding me, for as long as I can remember. I don’t know whether I can make sense of what’s happening in the world right now, and I can’t make sense of grief, nor fury, nor fear, and I can’t explain why terrible things happen, nor why leaders behave irrationally, cruelly, impulsively, and without regard for human life. I don’t know why. I don’t know, I don’t know. But I know, on a very small scale, that writing helps. Telling stories helps. As necessary as bread.

xo, Carrie

Thursday, Nov 28, 2019 | Big Thoughts, Book Review, Books, Confessions, Exercise, Feminism, Mothering, Politics, Space, Success, Word of the Year |

I’ve read some excellent books these past few months, all by women, mainly fiction. Most recently, I finished THREE WOMEN, by Lisa Taddeo, creative-non-fiction, and the kind of book a person wants to discuss afterward with someone else. In the absence of a book club, I bring my thoughts to you. (This is how compelling the book is: I was reading on the couch last weekend, sharing a blanket with my eldest daughter, when she suddenly said, “Wow that book must be good, Mom. You haven’t fallen asleep!”)

(Possibly related note: the book has a lot of graphic descriptions of sex. But in my interpretation, as you’ll see below, the sex stands in for desire more generally.)

THREE WOMEN is a book about women’s desire as examined through the lens of sexual desire(s) that our culture would call taboo. One woman defines herself as a submissive and has sex with other men and women while her husband watches or participates. One woman, in an almost-sexless marriage, has an affair with a former boyfriend after connecting on FB. One woman, as a high school student, was pursued by and sexually involved with a teacher, and when charges are pressed years later, the teacher is absolved and she is destroyed.

THREE WOMEN is a book about women’s desire as examined through the lens of sexual desire(s) that our culture would call taboo. One woman defines herself as a submissive and has sex with other men and women while her husband watches or participates. One woman, in an almost-sexless marriage, has an affair with a former boyfriend after connecting on FB. One woman, as a high school student, was pursued by and sexually involved with a teacher, and when charges are pressed years later, the teacher is absolved and she is destroyed.

But she had already been destroyed. (This is not a spoiler; the book’s propulsive nature relies on exploration of character rather than plot.)

The most interesting section, for me, comes in the epilogue, when the author unpacks, most explicitly, the subject she’s been examining, and reveals that this particular desire she’s been exploring throughout is an exemplar for anything a woman wants—desire, generally.

Her mother, dying, has something she agrees to reveal to her daughter. Something she wants to tell her.

Are you ready? She asked me.

Yes, I said. I got close to her face. I touched her cheek. It was still warm and I knew it wouldn’t be for long.

Don’t let them see you happy, she whispered.

Who?

Everyone, she said wearily, as though I had already missed the point. She added, Other women, mostly.

I thought it was the other way around, I said. Don’t let the bastards get you down.

That’s wrong. They can see you down. They should see you down. If they see you are happy, they will try to destroy you.

But who? I asked again. And what do you mean? You sound crazy.

Later, the author writes: “… we cannot exactly say that we expect to be happy.”

Finally: “There was a beauty in how little my mother wanted. There’s nothing safer than wanting nothing. But being safe in that way, I’ve come to know, does not inure you to illness, pain, and death. Sometimes the only thing it saves is face.”

So let’s talk about desire. Not sexual desire. Desire. Naming our hopes, our aspirations out loud.

Personally, I have trained myself to expect less, and perhaps also to want less, to make do with less, to make less a wonderful shelter, in a way, a goodness and righteousness, a way of life. I do believe, morally, in the ethic of more with less. But I also can see how lowering my expectations, and being afraid to name what I want (out loud or even quietly to myself) could make my whole life so much smaller. But if I name what I want, am I not guaranteeing I’ll never receive it? Jinx! Touch wood. I do this, when I accidentally state out loud something hoped-for.

In truth, I’m morally opposed to the idea of bottomless aspirational desire, of eternally needing and wanting more, which always seems to come at the expense of others. I disagree with inflicting harm on other people to favour one’s own pleasure. That is why the stories of two of the women in this book were more difficult for me to understand—acts of self-pleasure are rarely victimless. Can desire be healthy if acting upon it will damage those to whom we owe our loyalties and responsibilities?

I’ve been thinking about how comparing ourselves to others is a fast-track to misery. It’s a fast-track to bitterness, envy, and a form of self-loathing that we often turn outward on the object of our comparison. I fought these very feelings yesterday morning in a weight class at the gym, working out next to a woman who seemed effortlessly to wield weights heavier than mine, whose endurance was always greater than mine. My attention was divided, and I kept diminishing my own efforts, even while thinking things like: She must have more time to work out than I do, or even, It can’t be healthy to work out as much as she must, to be in such good shape. I also recognized, even as my thoughts ran in this direction, that any discontent I was feeling was so wholly not this stranger’s responsibility, but my own.

I wonder whether comparison whispers to us that we should have been wanting more all along, that our suppression of desire has cheated us somehow? Does it make us question our life choices? Recognize invisible alternate realities all around us that may already be closed to us?

Is our comparative envy perhaps also related to a scarcity of resources? For women, there is an extreme scarcity of resources around desire, success, and achievement. We have a very narrow window of acceptable achievement, and of the way to acceptably achieve. Naming our desires is not so straightforward. We have to be so careful not to name desires that would hurt others (as I said above), especially our children. We struggle, too, to claim our own successes. We work so hard to keep in balance all these pieces of ourselves — and our expectations for ourselves — that we inevitably fail on one important front or another.

We cannot exactly say that we expect to be happy. Is this a gift we could give to each other, especially as women? — admiration for each other’s strengths, in tandem with appreciation for our own.

xo, Carrie

Sunday, Nov 17, 2019 | Art, Big Thoughts, Exercise, Fire, Meditation, Peace, Politics, Running, Spirit, Stand, Winter |

I’ve been running a lot, and will continue to run a lot for as long as I can stave off injury and chronic pain, no matter the weather. Winter has descended early on Southern Ontario, and I’ll admit that it takes a little more gumption to layer up and run out into a stiff headwind over icy sidewalks. You have to really want to, for some reason beyond the running itself — and for me, that’s my mental health. Running clears my mind. Clears my anxieties. Makes me feel stronger, powerful.

But I do have to run early, it has to be the first thing I do upon waking, or I lose the gumption. I don’t mind running in the dark, oddly enough. My favourite path is reasonably well-lit, and I’ve come to love the quiet of the early morning, its solitude almost dream-like, the darkness a strange comfort, womb-like. There was little wind this morning, and I kept a steady pace, earbuds in, tuned to a podcast called Dolly Parton’s America, which at one point brought me to tears, as the host described the unexpected connections between Dolly Parton’s Tennessee mountain home, and his own father’s Lebanese mountain home. About how different musical instruments and rhythms, patterns and vocalizations find confluence across culture and time, come together, remind us of our common need for expression beyond words or even actions. So that happened on this morning’s run: I was crying.

And then, as I turned onto a busier stretch, I was yelling at the cars buzzing by, their noise and fumes drowning out the podcast.

Emotions: they’re all over the place. Where do they come from, where do they go?

When I got home, I replayed one section again, to drink in what Dolly Parton had said. I’m telling you: You have to listen to this podcast! I’m starting to believe that Dolly Parton is not only a brilliantly talented songwriter and musician, but also a wise, grounded human being, who is carrying a message for our moment that we’re having difficulty hearing. To paraphrase what the podcast’s host said: Dolly Parton is expressing an ethos, a spirituality, in which no one is cast out. No one is condemned from the community. She has her opinions, but she will also allow that you have yours; and she has a massive capacity to see the other, to understand complexity in human behaviour. (I wonder if this points to a difference between being an artist and being an activist; both are necessary and important to instigating and envisioning change, but the roles don’t necessarily overlap, because the strengths of an artist are different from the strengths of an activist. Their ways of framing experience often run counter to each other.)

I spent last week watching documentaries, having bought a pass to our local feminist film festival — founded by a friend nine years ago — which runs every November. I crammed in as many movies as I could: I saw a movie about the family of Colton Boushie, thrust into a public spotlight, speaking with clarity out of their pain; a movie about women incarcerated in New Brunswick, making art together, cast in and out of the system and trying to see their way clear; a movie about an Israeli family in which the father transitions to becoming a woman; a movie about an all-woman sailing team who sailed in a race around the world; a movie about Ruth Bader Ginsberg, and a movie about Toni Morrison. (What made it really special was that I saw each movie with a friend or with one of my two older kids.)

At the end of seeing all these movies, I said: How anyone makes it through this world whole is beyond me. And maybe we don’t. Maybe we don’t make it through this world whole. But there are moments of clarity, amidst the confusion. Moments when people are called by some force beyond themselves to take a stand. Moments when they call others in and hold them. Moments of forgiveness. Moments beyond pain and suffering. The victories might be small and temporary. But no matter.

If you pay attention to someone else’s story, you’ll see under the armour and bluster and noise to the complexity of need and of fear and of hope beneath. We all want a safe place to call home. We all want to feel safe, and loved, without condition. How can we be that for each other? It comes naturally to want to be that for my family and friends, but can I try, too, to be that for those with whom I have little connection and less understanding? Can I ask for the same in return?

xo, Carrie

Friday, Sep 27, 2019 | Big Thoughts, Current events, Green Dreams, Politics |

Today, I went to the climate protest in our town square. None of my kids went, and Kevin was working and couldn’t strike, so it was just me. We live nearby, and I walked, noticing people amassing, some with signs, many with children or pushing strollers. By sheer dumb luck, I ended up standing on a concrete riser closer to the front, where I could see some of the speakers. Drumming. Call and response. “What do we want?” “Climate action!” “When do we want it?” “Now!” And then a stripped-down orchestra appeared, led by a conductor, and they began playing Ode to Joy, quietly at first, a single cello, then more instruments joined, and at last, like magic, the choir burst out singing. I was right in the middle of it; I’d seen them filing in with their sheet music.

Goosebumps. I wished my kids had skipped school to experience this, too.

One speaker asked us to turn to someone else and say why we’d come. I turned to the woman behind me and introduced myself, and she introduced her son. I admired his handmade sign, covered in scribbles (he was 2 years old, at most). But I didn’t say why I’d come, nor did I ask her why she’d come.

At one point, the crowd start chanting something that I interpreted as HOPE. After calling this out for awhile, I realized everyone else was saying VOTE.

Oops.

Well, it was hope that got me out the door and into the crowd. At least, I think that’s what it was. I wonder whether recognizing and responding to the climate crisis is a matter of viewing everything through a different lens. There are so many things we’re blind to, until we learn to see differently (racism, misogyny, poverty, and the list goes on and on). We don’t know what we don’t know, in so many ways, and so often we don’t understand until we’ve experienced something up close, either personally, or in some other immersive way (side note: stories are powerful like this). My kids, yes the same ones who didn’t go to the protest, are seeing the world differently: my son, who can vote this fall, says he’s most interested in climate policies because the other stuff seems insignificant by comparison (jobs, the economy, taxes).

This one sign said: STOP LIVING IN YOUR FANTASY.

That got me. It is a form of fantasy to imagine we can keep living the way we’re living, especially here in Canada, where we consume far more than our fair share of pretty much everything. I didn’t make a sign, but I was thinking: WAKE UP!

I was also thinking: WHAT ARE YOU WILLING TO SACRIFICE?

But that’s more of a question for myself, a personal question. What happens after a protest? I feel overwhelmed and swamped with partial and seemingly insignificant choices — cooking vegetarian/vegan (which we often do), refilling plastic containers at the bulk store (ditto), walking more, driving less (but soccer fields are so far away!). Maybe I want to know that whatever I’m sacrificing will actually be consequential, rather than merely delusional. Rather than another form of fantasy. I want a road map. I want direction.

Also, I want leaders who do something. But what? What would I be willing to sacrifice?

xo, Carrie

Sunday, Jul 14, 2019 | Blogging, Politics, Spirit, Stand, Writing |

I’ve been sitting down to write this blog post for a few days, but it keeps changing on me. Circumstances keep changing. Time keeps moving and things keep happening, and I can’t decide what, exactly, I want to say. I even wondered, last night, whether maybe it was time to stop publishing random inner thoughts on a whim, sending them into the universe without taking time to reflect on why I’ve wanted to share what little I know (or think I know). But here I sit again, typing words into a blank rectangular space.

I’ve been sitting down to write this blog post for a few days, but it keeps changing on me. Circumstances keep changing. Time keeps moving and things keep happening, and I can’t decide what, exactly, I want to say. I even wondered, last night, whether maybe it was time to stop publishing random inner thoughts on a whim, sending them into the universe without taking time to reflect on why I’ve wanted to share what little I know (or think I know). But here I sit again, typing words into a blank rectangular space.

I write in other places too. I write in my notebook, in pen, words few people could decipher even if they tried. I like not knowing what will come of that material; I like knowing it’s likely nothing will come of it, and it will just exist as a muddy river of unfiltered thought.

I also write stories, using Scrivener or Word, and that always feels like I’m doing something different, too, than what I do here, on this blog. There, I have time, I take time, sometimes years, going over and over the lines of neatly spaced words. I polish. I revisit. I consider. I restructure. It’s satisfying, and while I do write these stories knowing they could be published, someday, the outcome is difficult to guess and in some ways doesn’t matter. I have to work them over till I feel done with them, or they’re done with me.

This blog is a different space. Immediate. Gratifying. Immediately gratifying. When I skim through the years’ worth of postings (nearly 11 years, now), it’s like looking through a scrapbook. Quite pleasant, though I don’t do it often. It can feel like I’m looking at a stranger’s life, in some ways. I’ve been and done many things in the past 11 years, I’ve had my enthusiasms, responsibilities, interests, routines. I’ve been knocked off the path by fortune and misfortune. As ever, I don’t know what happens next, exactly, but I trust that more change will come, and I’ll be pulled onward, to new (or seemingly new) revelations, interests, insights, and errors. There will always be something to write about, in one medium or another.

I had an experience on Friday night that disturbed me; I can’t think what to do about it, so I’m writing about it here. On Friday afternoon, I went to Stratford with my sixteen-year-old daughter, who is off to camp this weekend for a month; we saw Billy Eliot, a musical that confronts ideas about masculinity, among other subjects. That same evening, Kevin and I went and saw Booksmart, a movie about best friends graduating from high school, that was also endearingly, hearteningly queer-positive without making a big deal of it. I could think and imagine that the world was becoming (had become) a better place, a safer place. And then, almost as soon as we’d left the movie theatre, Kevin and I found ourselves in between two groups of young people who were shouting at each other. Actually, it was really only one young man who was doing most of the shouting, and what he was shouting was disturbing, bigoted, violent. He was with a group of other young men, and while I don’t think they participated, they also didn’t intervene. They all looked the same to me: white, early twenties, athletic, clean-cut. The angry guy was shouting past us, at a teenager in a red sweater who was standing some distance away with two friends, a young woman and a young man. It ws the boy in the sweater who was the target of the other man’s rage.

I don’t want to repeat the language used. It was derogatory and homophobic. And finally, the kid in the sweater, whose body language said that he was tired of this, weary, not quite resigned, shouted something back. And then the other guy really cut loose. One of the things he shouted at that point was “you little bitch.” I turned around when he said that, because I wanted to shame him, because I wanted him to know that people were paying attention, and the angry guy said, “Ha ha, not you, you’re fine, I was talking to that other bitch, the one in the red sweater.” And then he started shouting again, possibly because I lifted my middle finger to him (not my finest moment), although it’s equally possible he didn’t even notice the gesture, and was still shouting at the kid. Kevin and I kept walking, and the group of young men kept walking too, in the opposite direction, and I thought it would be okay now, probably, the shouting was over. We passed the boy in the red sweater with his friends, and I wanted to stop and say something, but I couldn’t think what. They seemed to be trying to put the scene behind them and decide where to go to get a drink.

I said to Kevin, “This is the world our kids will have to live in.”

And he said, “They’re already living in it. I’ve spent the weekend reading John Boyne’s The Heart’s Invisible Furies, which follows the life of an Irish man from birth till death; it’s also the history of gay rights in Ireland, from the time of the protagonist’s birth when men could be arrested for being in a homosexual relationship (or beaten up, murdered, blackmailed or banished), to the referendum that legalized gay marriage in 2015. The trajectory is optimistic (which isn’t giving too much away — you should read it), but having witnessed what could only be called a disturbing scene of homophobic rage on the sidewalk on Friday night, when I got to the novel’s happy ending this morning, I felt my heart sink rather than rise.

I’ve spent the weekend reading John Boyne’s The Heart’s Invisible Furies, which follows the life of an Irish man from birth till death; it’s also the history of gay rights in Ireland, from the time of the protagonist’s birth when men could be arrested for being in a homosexual relationship (or beaten up, murdered, blackmailed or banished), to the referendum that legalized gay marriage in 2015. The trajectory is optimistic (which isn’t giving too much away — you should read it), but having witnessed what could only be called a disturbing scene of homophobic rage on the sidewalk on Friday night, when I got to the novel’s happy ending this morning, I felt my heart sink rather than rise.

Things are better. And things are still frighteningly not better.

And I don’t know what to do about it. Life asks us to be the best we can be under the circumstances. To use what talents we’ve got. To be true to ourselves. I believe that, just as I believe that every human being deserves dignity. That dignity is always worth fighting for. But the obstacles are enormous, and when you get right down to it, the horror of it is that the obstacles are almost all human-made. I can’t possibly list all the indignities humans are forced to endure, all the ways humans prevent other humans from being free, but it’s everywhere I turn, especially when I turn on the news.

Tap, tap, tap. I’ve typed for too long, and come up with too little. But I guess I haven’t yet given up on pressing publish, even when I don’t quite know what I’m trying to say.

xo, Carrie

Page 4 of 10« First«...23456...10...»Last »

THREE WOMEN is a book about women’s desire as examined through the lens of sexual desire(s) that our culture would call taboo. One woman defines herself as a submissive and has sex with other men and women while her husband watches or participates. One woman, in an almost-sexless marriage, has an affair with a former boyfriend after connecting on FB. One woman, as a high school student, was pursued by

THREE WOMEN is a book about women’s desire as examined through the lens of sexual desire(s) that our culture would call taboo. One woman defines herself as a submissive and has sex with other men and women while her husband watches or participates. One woman, in an almost-sexless marriage, has an affair with a former boyfriend after connecting on FB. One woman, as a high school student, was pursued by