Category: Reading

Wednesday, May 16, 2018 | Art, Backyard, Big Thoughts, Confessions, Meditation, Peace, Reading, Spirit, Spring, Work, Writing |

I’ve been wandering through a book kindly sent to me by my Canadian publisher, Anansi, called The Enchanted Life: Unlocking the Magic of the Everyday, by Sharon Blackie. One of her suggestions is to find a place to return to, daily if possible, outside somewhere. A place where you can sit and simply be, and observe the natural world around you.

At first, I fantasized about biking or walking to a nearby park to sit beside the little creek that runs through it. But after several days of not biking or walking to the park to do this, I recognized that, as is often the case, fantasy and reality are two divergent paths. I do love my fantastical life, as lived in my imagination, but down here in reality, setting into action even small life changes requires a different toolbox.

Let me back-track.

I’ve just finished a three-day workshop on instructional skills (teaching skills), which was intensive, immersive, challenging, and rewarding. My takeaway could apply to life as surely as it applies to lesson-planning: to meet your objective, you need to identify it clearly, and create a process that leads you toward it.

So if my objective or goal is to sit outside in nature, and specifically, to find a place that I can return to daily if possible, what process would lead me toward that goal?

The answer turned out to be quite simple and straightforward, in this example. Best of all, it emerged naturally. After several days of not biking or walking to the park, one morning last week, I went to the back yard and sat down on a stump. Something must have called to me. I’d just walked my youngest up to meet his friends before school and instead of going into the house as usual, I went into the yard. The dog was with me, the air was sweet and temperate, and the buds were at their very newest, just barely emerging in a soft fuzz of yellow and green overhead. I took off my sandals and sat with bare feet in the grass. I closed my eyes. I listened to the birds and the traffic, and the jingle of the dog’s collar.

Aha. I’d found my spot, my place outside in nature to which I could return almost daily.

So I’ve been returning, not quite daily, but often enough to see already small changes in the grass and weeds and flowers. Today, I opened my eyes after a ten-minute meditation and thought, This is my work, too.

It might not look like work. And it might not register as work, because it is so full of pleasure. But I know that in order to write, to create, and yes, to teach, I must be contemplative. I must reflect. I must be quiet and listen and observe and watch, and be. In this quiet place — quiet on the inside, I mean — such wonderful fantastical ideas play across my mind. So much of my work happens in the imagination. So it is inevitable that some of these ideas will capture my interest enough to be named as possibilities to pursue here in the real world.

The process by which these possibilities are achieved seems to me both practical and mysterious. We are ever-changing, and our needs and interests are ever-shifting. The process by which we move toward goals, and the goals themselves, also change and shift, as they must; often unconsciously. I like when I can recognize what’s happening and celebrate it. I like when I can recognize what I want to have happen, and can tweak my daily routine to see it come about.

Exercise is one area where it’s been easy for me to set goals and achieve them. These goals have changed and continue to change, affected by injury, age, and intention. I am aware of both the changing nature of my goals, and of the changing processes required to meet them. Therefore, I feel ease and flexibility in my approach. Parenting is the same for me, somehow; ever-changing, but replete with clear objectives: to support and to love. The work might be hard, but the meaning of the work is clear.

Naming a goal is perhaps the most difficult step. Narrowing it down. Understanding it, understanding why you want this particular change, or outcome. Committing to it. Why do I want to sit quietly in nature as often as possible? Immediately, answers float to the surface. Because it calms me, because it connects me to something bigger than myself, because it clears my mind. It helps me to see the bigger picture. It feeds my spirit.

What if I were to name a different goal: to publish another novel. I’ll confess that my motives feel less clear in this example, even though the goal appears straightforward. Certainly, I understand the process. But the underlying objective, the greater why of it all, eludes and troubles me; no doubt it’s different now than it was when I first published. And so I wonder … Is it to further my professional career, both as a writer and a teacher? Is it to share knowledge in a creative way? To entertain an audience? Is it to earn a living? Is it to publicly express ideas important to me that can’t be otherwise expressed? Is it to garner attention and feed my ego? (How I fear this last intention, how I fear it might be a secret intention I hide even from myself.)

It seems to me that writing a novel expresses a different intention than publishing a novel. I’m at ease with the former; I’m uncomfortable with the latter.

Yet I want to name it as a goal. I want to publish another novel.

Because …

I want to learn from the process, again, how to go forth into the world carrying an idea, and how to share it openly, generously, without fear or shame. I want, also, to polish an idea until it becomes a publishable book, full of breathing characters that live beyond me.

Somehow, my body understands that sitting quietly on a stump is part of the process that will lead me there.

xo, Carrie

Thursday, Nov 9, 2017 | Art, Big Thoughts, Meditation, Peace, Reading, Spirit, Teaching, Writing |

In the past couple of creative writing courses I’ve taught, I’ve devoted an entire class to listening to and writing fairy tales. Why? Sometimes I introduce an exercise without fully understanding its necessity, until I’ve been through it several times. After my fairy tale class yesterday, my brain was spinning, like I’d learned how to spin flax into gold. I may not entirely understand why the fairy tale is so valuable to listen to and enter into, but I’m getting closer.

Fairy tales are full of archetypal imagery: images that are powerful and timeless, even if they may be interpreted differently by different cultures and in different eras. Brothers and sisters; transformations; talking beasts; wise women and witches; kings and queens; red shoes; axes; forests; water. As we wrote our own fairy tales, some of these images no doubt found their way into our stories, and we knew they had meaning beyond themselves, we understood it at gut level. A dark forest conjures a meaning different from a river; the moon means something different from the sun; the power of a witch is different from the power of a king or a queen. Maybe we also understood that the meaning of these images was somehow malleable, too, and that we could work with it, we could subvert it, we could make it our own—we understood that meaning shifts. Sometimes it’s even our duty to shift meaning or fight against it.

Fairy tales are by their nature grim, even gruesome; the characters suffer horrors and sorrow that is difficult to comprehend. And yet the stories are told in a way that makes them enjoyable to listen to—not frightening, but compelling. One of the hardest tasks as a writer is to write about trauma without traumatizing the reader: fairy tales do exactly that. How do fairy tales protect us, even as they reveal traumatic narratives? Perhaps it is in part our detachment from their one-dimensional characters. But I think protection also relies on the use of archetypes to contain and control horror, and shape meaning.

What is the difference between meaning that is political or ideological and meaning that is literary? The world is not magical. In other words, what happens to us is not meaningful, in and of itself. We make it magical: we create the meaning. We impose shape onto the events we witness, onto our own experiences, onto the random gathering of routines, activities, sights and sounds, interactions and reactions that make up our lives—much of what falls through and into our lives is like the weather, out of our control. This could be terrifying, paralyzing. It is not a truth our brains accept easily; in fact, our brains are built to create narrative to explain the randomness, to comfort ourselves, in order to survive and to thrive. The same source of comfort drives our impulse toward religion, politics, and poetry: narrative. We need narrative because we need meaning. Meaning comes from shape, pattern, images that carry thematic weight, from threads being pulled together to weave a tapestry that is so satisfying to our brains that we don’t care that it’s not real because it feels real—it feels as it should.

Why do we seek to understand the motive of a man wielding an AR-15 in a church? (I’ve been wondering and wondering about this, because in my opinion, trying to pin down a motive in cases like this is a waste of our collective energy; but most news media would disagree.) There may be a fundamentally human reason driving this search: because without motive there’s no sense of cause and effect, there is only shapeless unformed chaos resulting in death and grief. Audiences want their stories to make sense, and the news media are storytellers and we are their audience. Think of all the different ways we impose narrative on the world around us—my interest is largely literary, but political narratives are inevitable and create competing storylines that truly fail to intersect. Some narratives exclude, lock out, imprison rather than connect.

How can literary narratives help us? By creating empathy—through windows and doors, through the lens of another’s eyes. By refusing to be ideological. By appealing to our human frailty and flaws—by showing us our possibilities and our hopes, and our failures. By releasing us from our humanness, too, sometimes, the way that fairy tales do. Fiction is inherently unrealistic (even so-called realism). Fiction will always be much more and much less than reality is—it contains both too much or too little of reality to be real. Fiction is interpretation. Fiction pushes the writer to identify what matters in whatever moment is being described. It creates magic inside of us all of a sudden! We become magical when we write and also when we read, because we are transforming what is into what could be—a recreation that has substance, shape, and meaning.

Something from something, as Etger Keret writes.

I wrote this in a white heat of emotionless thought after yesterday’s class, as if it were tearing from me whole: the reason I write, the power of writing, the value of it.

“The world is not magical. We make it magical all of a sudden inside of us.” – Silvana Ocampo

Write these words on my heart.

xo, Carrie

Friday, Jul 14, 2017 | Art, Big Thoughts, Books, Confessions, Publishing, Reading, Spirit, Teaching, Work, Writing |

The longer I teach, the more I learn.

If I were to write a dissertation, now, my subject would be the short story. I would take a scalpel to the form, carve three-dimensional paper sculptures to show how beautifully various the short story can be. My focus, as a reader and a writer, has long been on Canadian literature, but the more widely I read, the more I wonder what Canadian literature stands for. Where are we right now? What are we lacking? Are we constrained by our Canadian-ness, because our patron is the state? Our violence is secretive and shameful. We don’t dare feast or riot. We would never burn the house down, and if we did, we’d make sure no one knew it was us. Also, outwardly, we appear reasonably satisfied with this state of affairs.

I could be wrong. I could be entirely very very wrong. Generalizations are almost certainly wrong, at least to some degree.

But here’s what I’ve learned, from teaching. For the past five years, I’ve assigned Canadian short stories for my students to read and discuss, and my students’ complaint has been consistent: why are these stories so similar? At first, I was baffled: the differences between the stories were so clear to me; subtle, perhaps, but clear. But as I’ve started to read and assign stories from international writers, some in translation, I’ve come to understand that my students were more perceptive than I. This is not to dismiss my beloved Canadian stories. But I see, now, that there is a world of stories out there that are different and not just in subtle ways, but in juicy, technically audacious ways: stories that are ugly, ungainly, colourful, lawless, unconventional, impolite, rowdy, hungry. Imperfect. Stories that dare to be disfigured, furiously cryptic, ridiculous, structurally untidy, fascinating, open, broken, big. Stories that can take the criticism, because they’re out there doing the dirty work, and they’ve got more important things to worry about.

The world is waiting to be read.

I can’t pretend to know what Canadian literature stands for, nor what it lacks, nor what it needs. I think we are in troubled waters, troubled times, but I’ve been devoted to CanLit for my whole life, steeped in the stuff, and this is my trouble, too. Times of transition are always troubled times. I believe this. Transition is what gets us somewhere new. Truth and reconciliation: painful. It’s painful to be wrong, but how much more painful is it to be a child of 12 for whom suicide is the answer to their pain, how much more painful to be this child’s family, community. This is our country, right now. This is Canada. And somehow, I think it’s our literature, too. Now is not the time to turn more inward, to hide away, to ignore, not listen, not try. It feels imperative — to try. To pay attention.

I want to write stories like the ones I’ve been reading from around the world, and I can try. I may not be able to, but others will. If I’m a very fortunate teacher, maybe my students will. Meanwhile, I can keep learning, listening and reading.

xo, Carrie

Thursday, Jun 1, 2017 | Books, Confessions, Reading, Teaching, Work |

I realize, coming into my office this morning, that my reading life is a mirror for my actual life, and at the moment both appear scattered, reflective of broken or partial attention. I have never in my life had so many half-read books stacked all around me, on my bedside table, the dining-room table, a stool in my office, in my purse (the big one), on the staircase. Here is a list:

I realize, coming into my office this morning, that my reading life is a mirror for my actual life, and at the moment both appear scattered, reflective of broken or partial attention. I have never in my life had so many half-read books stacked all around me, on my bedside table, the dining-room table, a stool in my office, in my purse (the big one), on the staircase. Here is a list:

On the stairs, with the intention of being carried up to the bedside table (already totteringly tall): Elena Ferrante’s My Days of Abandonment, abandoned early on; American War, by Omar Al Akkad, which I started yesterday while sitting on these very stairs.

On my bedside table (this includes only the books at the top of the pile): Jesmyn Ward’s Salvage the Bones, which I was enjoying, but that was last month, and I’ve only just remembered that I was reading it; Being Mortal, by Atul Gawande, of which I read the last few chapters, then tried to start at the beginning, probably a mistake. Both of these are buried under the Rachel Carson biography, not yet finished—my interest waning, perhaps unfairly, with her growing success.

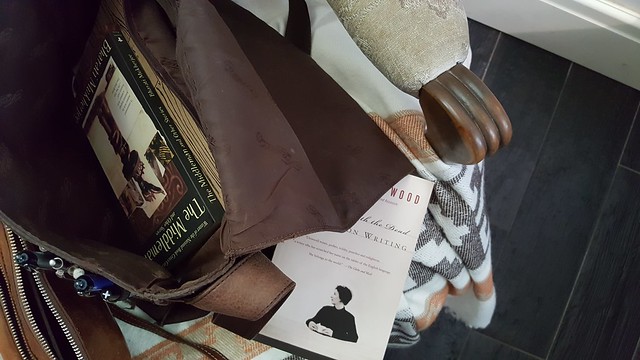

Beside me in the office on my rocking chair, we find Margaret Atwood’s Negotiating with the Dead. The folded-down page corner informs me that I’m mid-way through, but as I skim through chapters apparently already read, I realize how little I’ve retained and long to read them again, as if gazing upon fresh material. Also on the rocking chair, tucked into my purse (the big one): The Middleman, by Bharati Mukherjee.

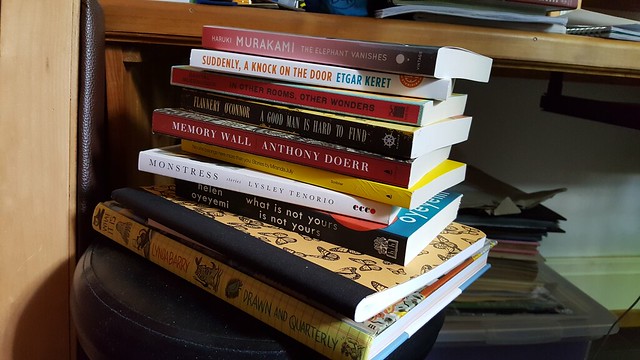

Over here on the stool, on the other side of my desk: Monstress, by Lysley Tenorio; In Other Rooms, Other Wonders, by Daniel Mueenuddin; Etger Keret’s Suddenly, A Knock on the Door; and Haruki Murakami’s The Elephant Vanishes.

Out there on the dining-room table: Lydia Davis’s Collected Stories, with a pretty red ribbon repurposed as a bookmark, denoting where I stopped in the middle of story (almost impossible to manage, given that so many of her stories are breathtakingly brief). Also on the table, Destination Unstoppable, by Maureen Monte, bought after hearing her interviewed on a sports podcast, thinking it might make me a better soccer coach; but it’s a self-published book with the obvious self-published problem of not having been edited, a flaw that kills the transmission of most decent ideas, at least those presented in book-form.

Is that all? I also have some re-reading to do for my creative writing class, and 125 poems to read, comment on and somehow apply marks to, as of tomorrow at midnight.

In the bathroom, there are New Yorker magazines with many half-read articles marked with folded pages. On my phone, I have access to even more articles, including in-depth ones that I want to read, such as an interview with Lydia Davis in the Paris Review (see book waiting on the dining-room table).

Rare photo evidence of this child reading a book.

What of this is my addled brain retaining? I dip in, with pleasure and surprise, images flicker through my brain, some hold, briefly alight; and I am interrupted, pulled back out. What am I accumulating to use, to inform, to enjoy?

Where is the through-line in this mess of partially digested images and voices? What am I keeping? What does this tell me about my life, right now?

Scattered.

xo, Carrie

Tuesday, May 23, 2017 | Big Thoughts, Book Review, Books, Feminism, Green Dreams, Peace, Reading, Spirit, Word of the Year, Writing |

On the weekend, I walked to the library with my elder daughter. While she browsed in the non-fiction stacks — the theoretical physics section — I played a little game that has served me well over the years: I wandered a little further (no theoretical physics for me) and plucked titles at random from the shelves, my choices based only on title or subject. In quick succession, I skimmed and rejected two books on Scottish folk and fairy tales, but my third choice had me sitting cross-legged on the floor, entranced.

On the weekend, I walked to the library with my elder daughter. While she browsed in the non-fiction stacks — the theoretical physics section — I played a little game that has served me well over the years: I wandered a little further (no theoretical physics for me) and plucked titles at random from the shelves, my choices based only on title or subject. In quick succession, I skimmed and rejected two books on Scottish folk and fairy tales, but my third choice had me sitting cross-legged on the floor, entranced.

It was a biography of Rachel Carson, the American scientist who became famous for her books about the sea and the beauty of the natural world, and who is remembered now as the author of Silent Spring, a book that warned the public about the dangers of pesticides and other chemicals. Silent Spring was published in 1962; Rachel Carson died in 1964 of cancer. If you google Rachel Carson, you will find that to this day she is reviled in some circles as a “feminizi ecoterrorist.” The biography, Witness for Nature, by Linda Lear, and published in 1997, is a little more nuanced. It evokes a portrait of a self-effacing, deeply intelligent, patient, hard-working woman who was led by her love of nature and science to become outspoken on conservation issues. Rachel Carson began her career as a government biologist, writing educational pamphlets on a variety of subjects. But she’d always wanted to be a writer. Science became her subject. And with enormous effort and obsessive care, Rachel Carson fashioned a successful literary career; eventually, she became successful enough that she could afford to resign from her government post, in her mid-40s, to devote her life to writing about science in poetical narratives that appealed to a broad audience.

It goes without saying that Rachel Carson was an unusual woman for her era. What strikes me most, however, is how fresh and relevant her message remains today.

Even though the book was an enormous tome, I decided to check it out and carry it home, and I spent the weekend reading it with pleasure. I’d forgotten how much I enjoy biographies, especially of writers. I look for clues, I nod in recognition, or admit to envy for those who have a knack for self-promotion. Rachel Carson’s attention to detail, her push for publicity, her irritation with her first publisher, who failed to promote her first book — all of this impressed me. She had a vision for the entire publishing process and she saw it through, little deterred by criticism, yet open to critique, actively seeking it out, so as to better her own work. She also frequently turned down promotional opportunities, speeches, honorary degrees, etc., to preserve time and space for her research and writing. She knew how to say no. (Is it too late for me to learn?)

Rachel Carson lived with her mother, who kept house for her; she was the main breadwinner for her family, which included at times her older sister and brother, mother and father, and later, her orphaned nieces. She did not marry, had no children. Our lives, in their domestic details, do not much meet and overlap.

But reading about her life has got me thinking about the importance of devotion to a subject; no, the critical imperative of devoting attention to a subject, if one is to hope to learn, to understand, to teach, to share knowledge, to find solutions to human problems large and small. Our lives on earth depend upon it. We cannot be lead by those who would ignore deep, complex knowledge in favour of simplistic superficial fixes. We cannot give power to ignorance. (Too late? Well, then let’s stand true against powerful ignorance.)

Here is Rachel Carson on her belief in the universal accessibility of science:

Here is Rachel Carson on her belief in the universal accessibility of science:

“We live in a scientific age; yet we assume that knowledge of science is the prerogative of only a small number of human beings, isolated and priestlike in their laboratories. This is not true. It cannot be true. The materials of science are the materials of life itself. Science is part of the reality of living; it is the what, the how, and the why of everything in our experience. It is impossible to understand man without understanding his environment and the forces that have molded him physically and mentally.”

Here is Rachel Carson on the human tendency to focus on egocentric problems, and to fail to see our place in the vast sweep of time:

“Perhaps if we reversed the telescope and looked at man down these long vistas, we should find less time and inclination to plan for our own destruction.”

And here is Rachel Carson on the danger of seeing humankind as separate from nature:

“Mankind has gone very far into an artificial world of his own creation. He has sought to insulate himself, in his cities of steel and concrete, from the realities of earth and water and the growing seed. Intoxicated with a sense of his own power, he seems to be going farther and farther into more experiments for the destruction of himself and his world.”

Her solution? Wonder and humility.

“Focus attention on the wonders of a world known to so few, although it lies about us everyday.”

Recognize your place in the grand sweep of time. Know yourself to be part of the natural world. Wonder at your participation in the cyclical turnings. In this way, by becoming very small, by being a piece of something much larger than yourself, you will be of the world around you, not against it. I am fascinated by her repetition of the word “destruction” — her insistence that the human belief that we are above nature, not of nature, springs from a dangerously destructive impulse, that it invents and experiments with destruction.

I love when a book finds me.

xo, Carrie

Wednesday, Mar 16, 2016 | Books, Confessions, Holidays, Reading |

I haven’t been inspired to write much this week. We are on March break in Canada, which means the kids have the week off school. Yesterday, I basically drove back and forth between our house and indoor sports fields: twice to basketball camp, once to a soccer game, and once more to take a child to a referee clinic and then pick her up. I considered, briefly, going to one more indoor field to watch one more soccer game, but couldn’t muster the strength. Instead, if memory serves, I sat in my office in my coat and looked at videos on FB. People post a lot of videos there, now. I reposted one, which shows the faces of every woman who has won a Nobel prize. So I’m part of the problem, not the solution.

The solution, I find, is not to go onto FB. In fact, when I’m writing well, I’m not tempted and check it rarely. I go there to be entertained, and I’m aware of that.

On the weekend, I read Sarah Waters’ The Paying Guests, which I couldn’t put down, plus it was scaring me, so I had to read it during daylight hours, not before bed. I rarely read books during the day, almost only before bed. This seems ridiculous given that every day I read magazines (including The New Yorker, Harper’s, The Atlantic, Macleans) and the daily newspaper (The Globe and Mail). I’m reading all day long! So why not books? Why reserve book-reading for just-before-sleep? I wonder if it’s because books are so consuming? I need to fall asleep in order to stop reading them. If I were to pick up a book during the day, I wouldn’t want to put it down. Newspapers, magazines, these are meant to be digested in short spurts, glanced at; but a book is immersive.

Maybe people join book clubs to give themselves permission to sit and read a book, especially fiction. There’s almost something illicit about the attention a book demands. You’re going to another world, you’re time-travelling, you’re living inside someone else, seeing through another’s eyes, you’re lost to the present moment. I have found books to be healing, necessary, important. But despite this, my mind categorizes books as indulgences, sweet treats, guilty pleasures. I have to let myself go in order to enjoy them. Maybe I should do that more often … especially during a week when I haven’t felt much like writing.

xo, Carrie

Page 5 of 17« First«...34567...10...»Last »