Category: Feminism

Friday, Jul 7, 2017 | Chores, Exercise, Family, Feminism, Holidays, Kevin, Kids, Lists, Mothering, Organizing, Parenting, Summer, Writing |

Hey, happy summer, everyone!

Hey, happy summer, everyone!

School ended a week ago, and I would like to report on our free-range plan for the summer of 2017, but I keep being interrupted by the free-range children. Kevin has been working from home in his new “office,” on the upper deck of the front porch, but this morning he had to go to his office-office, so it’s just me and the kids and dogs, with no buffer in between. Since sitting down, I’ve fielded the following questions/observations: a) how do you turn the hose off in the back yard? b) where is my swim suit? c) do we have the third book of Amulet? I already looked on the upstairs shelf. d) hey, the NDP is having a leadership race [from the child reading the newspaper at the dining-room table behind me].

Could be worse. And I’m just blogging. If I were trying to write, my response would be ARGHH!!!

In fact, Kevin has been home because I have been trying to write this week, trying to shape my months of handwritten, circling narrative into novel-form, and I’m at the point in the project where, frankly, it all falls apart. My current philosophy (and by current, I mean, as of yesterday afternoon), can be summed up thusly: just finish it, including all of your bad (wild, implausible) ideas, and see what happens. As I counselled a student yesterday in my office: the perfect story you’re holding in your head has to get out of your head in order for others to read and experience it—and in order for that to happen, you have to accept that your perfect story will be wrecked in the process, at least to some degree. You can’t take that perfect story out of your head and place it on the page intact. No one can. But there isn’t another way to be a writer. Let your perfect imaginary story become an imperfect real story.

I’m trying to take my own advice.

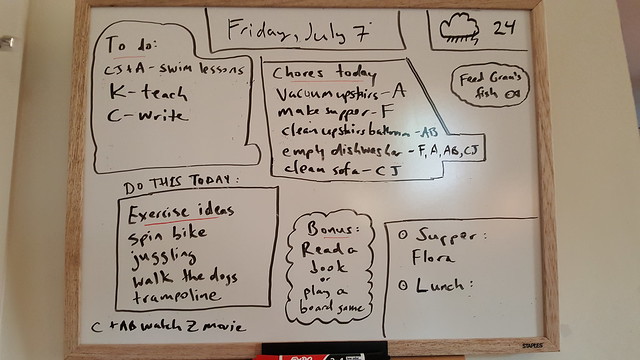

Here. I present to you something that brings me joy every time I see it. [insert little arrow pointing up] You could call it a chore board, but that’s a rather pedestrian title given the magic it has created in our house this past week. Every morning, I write down chores that need doing, and the children sign up for them; the later you sleep, the less appealing your chore. Today, the last one out of bed got: “clean upstairs bathroom.” We’ve also banned video games or shows between the hours of 9am – 4pm. (Exception: older kids use their cellphones; I’m not great at monitoring this.) It’s still early days, but the chores are getting done with minimal fuss, perhaps because the assignment comes from the board, not from a nagging parent.

Here. I present to you something that brings me joy every time I see it. [insert little arrow pointing up] You could call it a chore board, but that’s a rather pedestrian title given the magic it has created in our house this past week. Every morning, I write down chores that need doing, and the children sign up for them; the later you sleep, the less appealing your chore. Today, the last one out of bed got: “clean upstairs bathroom.” We’ve also banned video games or shows between the hours of 9am – 4pm. (Exception: older kids use their cellphones; I’m not great at monitoring this.) It’s still early days, but the chores are getting done with minimal fuss, perhaps because the assignment comes from the board, not from a nagging parent.

Other summer observations: I’m not waking up very early. This is the natural consequence of staying up too late! In addition to the kids running riot over regular bedtime hours, and soccer practices lasting (unofficially) till sundown, I’ve also been staying up late to watch feminist movies. Must explain. I’ve gotten myself, somewhat unofficially (?), onto the board of a locally run feminist film festival and my inbox is now full of films to view and consider. (Anyone out there with ideas for must-see recent feminist films, give me a shout!) But the only time I have to spare for movie-watching is rather late at night, post-soccer practice. Ergo, not waking up early. Ergo, early morning exercise-rate, somewhat reduced.

Other summer observations: I’m not waking up very early. This is the natural consequence of staying up too late! In addition to the kids running riot over regular bedtime hours, and soccer practices lasting (unofficially) till sundown, I’ve also been staying up late to watch feminist movies. Must explain. I’ve gotten myself, somewhat unofficially (?), onto the board of a locally run feminist film festival and my inbox is now full of films to view and consider. (Anyone out there with ideas for must-see recent feminist films, give me a shout!) But the only time I have to spare for movie-watching is rather late at night, post-soccer practice. Ergo, not waking up early. Ergo, early morning exercise-rate, somewhat reduced.

Oh, I want to mention one more lovely addition to the routine: a shared journal with my eldest daughter. We write back and forth to each other, or draw back and forth, or quote poetry back and forth. I’ve devised a quick summarizing list that is easy to complete, if we’re writing late at night, when we’re too tired for originality. Filling out the list has become something I look forward to, every day. My answers are sometimes long and rambling, sometimes brief. (Want to try answering the list in the comments, below? I would love that.)

Oh, I want to mention one more lovely addition to the routine: a shared journal with my eldest daughter. We write back and forth to each other, or draw back and forth, or quote poetry back and forth. I’ve devised a quick summarizing list that is easy to complete, if we’re writing late at night, when we’re too tired for originality. Filling out the list has become something I look forward to, every day. My answers are sometimes long and rambling, sometimes brief. (Want to try answering the list in the comments, below? I would love that.)

- Something that surprised you today.

- Something you’re proud of today.

- Something silly.

- Something happy.

- Something sad.

- Something you’re thankful for today.

I will return with deeper thoughts (or not) as the free-range summer permits.

xo, Carrie

Tuesday, May 23, 2017 | Big Thoughts, Book Review, Books, Feminism, Green Dreams, Peace, Reading, Spirit, Word of the Year, Writing |

On the weekend, I walked to the library with my elder daughter. While she browsed in the non-fiction stacks — the theoretical physics section — I played a little game that has served me well over the years: I wandered a little further (no theoretical physics for me) and plucked titles at random from the shelves, my choices based only on title or subject. In quick succession, I skimmed and rejected two books on Scottish folk and fairy tales, but my third choice had me sitting cross-legged on the floor, entranced.

On the weekend, I walked to the library with my elder daughter. While she browsed in the non-fiction stacks — the theoretical physics section — I played a little game that has served me well over the years: I wandered a little further (no theoretical physics for me) and plucked titles at random from the shelves, my choices based only on title or subject. In quick succession, I skimmed and rejected two books on Scottish folk and fairy tales, but my third choice had me sitting cross-legged on the floor, entranced.

It was a biography of Rachel Carson, the American scientist who became famous for her books about the sea and the beauty of the natural world, and who is remembered now as the author of Silent Spring, a book that warned the public about the dangers of pesticides and other chemicals. Silent Spring was published in 1962; Rachel Carson died in 1964 of cancer. If you google Rachel Carson, you will find that to this day she is reviled in some circles as a “feminizi ecoterrorist.” The biography, Witness for Nature, by Linda Lear, and published in 1997, is a little more nuanced. It evokes a portrait of a self-effacing, deeply intelligent, patient, hard-working woman who was led by her love of nature and science to become outspoken on conservation issues. Rachel Carson began her career as a government biologist, writing educational pamphlets on a variety of subjects. But she’d always wanted to be a writer. Science became her subject. And with enormous effort and obsessive care, Rachel Carson fashioned a successful literary career; eventually, she became successful enough that she could afford to resign from her government post, in her mid-40s, to devote her life to writing about science in poetical narratives that appealed to a broad audience.

It goes without saying that Rachel Carson was an unusual woman for her era. What strikes me most, however, is how fresh and relevant her message remains today.

Even though the book was an enormous tome, I decided to check it out and carry it home, and I spent the weekend reading it with pleasure. I’d forgotten how much I enjoy biographies, especially of writers. I look for clues, I nod in recognition, or admit to envy for those who have a knack for self-promotion. Rachel Carson’s attention to detail, her push for publicity, her irritation with her first publisher, who failed to promote her first book — all of this impressed me. She had a vision for the entire publishing process and she saw it through, little deterred by criticism, yet open to critique, actively seeking it out, so as to better her own work. She also frequently turned down promotional opportunities, speeches, honorary degrees, etc., to preserve time and space for her research and writing. She knew how to say no. (Is it too late for me to learn?)

Rachel Carson lived with her mother, who kept house for her; she was the main breadwinner for her family, which included at times her older sister and brother, mother and father, and later, her orphaned nieces. She did not marry, had no children. Our lives, in their domestic details, do not much meet and overlap.

But reading about her life has got me thinking about the importance of devotion to a subject; no, the critical imperative of devoting attention to a subject, if one is to hope to learn, to understand, to teach, to share knowledge, to find solutions to human problems large and small. Our lives on earth depend upon it. We cannot be lead by those who would ignore deep, complex knowledge in favour of simplistic superficial fixes. We cannot give power to ignorance. (Too late? Well, then let’s stand true against powerful ignorance.)

Here is Rachel Carson on her belief in the universal accessibility of science:

Here is Rachel Carson on her belief in the universal accessibility of science:

“We live in a scientific age; yet we assume that knowledge of science is the prerogative of only a small number of human beings, isolated and priestlike in their laboratories. This is not true. It cannot be true. The materials of science are the materials of life itself. Science is part of the reality of living; it is the what, the how, and the why of everything in our experience. It is impossible to understand man without understanding his environment and the forces that have molded him physically and mentally.”

Here is Rachel Carson on the human tendency to focus on egocentric problems, and to fail to see our place in the vast sweep of time:

“Perhaps if we reversed the telescope and looked at man down these long vistas, we should find less time and inclination to plan for our own destruction.”

And here is Rachel Carson on the danger of seeing humankind as separate from nature:

“Mankind has gone very far into an artificial world of his own creation. He has sought to insulate himself, in his cities of steel and concrete, from the realities of earth and water and the growing seed. Intoxicated with a sense of his own power, he seems to be going farther and farther into more experiments for the destruction of himself and his world.”

Her solution? Wonder and humility.

“Focus attention on the wonders of a world known to so few, although it lies about us everyday.”

Recognize your place in the grand sweep of time. Know yourself to be part of the natural world. Wonder at your participation in the cyclical turnings. In this way, by becoming very small, by being a piece of something much larger than yourself, you will be of the world around you, not against it. I am fascinated by her repetition of the word “destruction” — her insistence that the human belief that we are above nature, not of nature, springs from a dangerously destructive impulse, that it invents and experiments with destruction.

I love when a book finds me.

xo, Carrie

Wednesday, Mar 1, 2017 | Adventure, Big Thoughts, Confessions, Dogs, Feminism, Friends, Spirit, Stand, Word of the Year |

Just realized why this morning is feeling emptier than usual. For the past couple of months, I’ve spent Wednesday and Thursday mornings tutoring a new neighbour in ESL, and as of Monday, she’s attending formal ESL classes, which was always the goal. My intention was only to tide her over while she waited to get into the program.

Last week, we spent Thursday morning walking and riding the bus together, so her new route to school would become familiar. The next day, I listened to The New Yorker’s fiction podcast; the February post is Junot Diaz reading Edwidge Danticat’s story “Seven.” At the story’s end, two characters, who are immigrants from Haiti, ride the bus together. The phrase that spoke to me was: trying to see through her eyes.

I spent Thursday morning trying to see through my friend’s eyes, and it seemed that although we moved through the same physical space together, what we saw and heard did not mean the same thing to both of us. I’ve been thinking about this a lot. How privilege, skin colour, gender, age, wealth, familiarity, health, past experiences alter the world as we move through it. We exist in relation to what surrounds us, and in relation to how we perceive and are perceived.

Here’s what I wrote after listening to “Seven.”

When I am with my friend, I feel as though I am almost wearing her skin, her headscarf, I feel the exposure and vulnerability of being a newcomer, unaccustomed to the weather, to the language, to what is safe and what is dangerous. As we walk along a sidewalk, I see she fears the big black dog whose owner clips its collar to a leash on our approach — she recoils as she passes the dog, politely pulled off the sidewalk by the owner, who says good morning. But she does not seem to fear the white man and woman who come toward us with dyed and shaven hair, who I fear might be skinheads. Instead, I recoil.

Later, as we arrange ourselves on the bus, it is I who stagger unsteadily to a seat, uncertain of my balance, while my friend stands braced against the stroller and a pole, concerned for me. Her face is tired. She has been in Canada for almost three months. I think suddenly, she is tough, tougher than I can guess, tougher than me. All this time, I have wanted to protect her, but as I see her now I am ashamed to have been so reductive. She has told me about the guns coming to Syria, bang bang. She has endured more than I can imagine. Even so, I recognize her anxiety as she tries to orient herself. I want to assuage it, to reassure her.

I tell her, This is the stop. I pull the line and stand. The men move out of our way to let the stroller by. I want to help her lift the stroller, but she doesn’t need my help. We begin to walk. She sounds out the letters on the building across the street: “Don McLaren Arena.” Yes, I say, ice skating. I mime ice skating. She laughs and I think she doesn’t understand so I continue to mime. She taps her head. What she’s trying to tell me is that she will remember “Don McLaren Arena” — this is her stop. Great idea! I stop ice skating and exclaim.

We walk in silence for awhile. I don’t want to fumble with my phone and Google translate in this bright sunshine. I see a man walking a big black dog, ahead, different man and dog. They are walking on a cross pass away from us. In Syria, dogs inside the house? I ask. She laughs, No! Brother, chickens, sheep, dog, she says. Outside. I tease her: Maybe someday, you will have a dog. In Canada, so many people have dogs and cats. No, no, no, she says. No dog, no cat. A bird, she says to me.

I can see her face, turned toward me, smiling, an objectively beautiful face, no makeup, clean and memorable. She is wearing a light-coloured headscarf.

A bird, I say.

A bird, she agrees. We walk past Tim Horton’s where she and her husband have come to buy coffee and roll up the rim to win. He won another coffee. She was hoping for a car, a TV. But just a coffee. No one wins the car, I tell her. She tells me that a little dog scared their daughter, who is five, who began to scream in fright, and the dog’s owner, a woman, picked up the dog and held it in her arms. It was okay? I ask. It was okay.

My friend is opening up the world to me. I see that I can’t see through her eyes, though I try, though I want to. I can only walk beside her, often in silence. Wondering what this place looks like through her eyes. Is it ugly or beautiful? Welcoming or closed? Is it safe or dangerous? Is it home? Could it be home? Everything looks both brighter and starker when I’m walking beside her. There is a clarity to the light, and a barrenness, as if the objects and structures are being stripped back to their bones.

The light is bright for February, and we are warm. Even my friend, wrapped in her black coat, always cold, admits that she is now warm. The baby starts to fuss as we near their apartment. I don’t want to say goodbye. It seems I receive as much from her friendship as she could possibly receive from mine, because I enjoy her company, because I am happy when I am with her, more curious, more alert, more aware, because even a bus ride feels purposeful, somehow, when I’m trying to see through her eyes.

xo, Carrie

Tuesday, Jan 31, 2017 | Big Thoughts, Feminism, Peace, Politics, Spirit, Stand, Word of the Year |

I don’t know if this is a good state in which to begin a blog post, while sobbing over today’s newspaper, but I’ve been silent because I don’t know where to begin, not because I have nothing to say, so I will begin here.

I don’t know if this is a good state in which to begin a blog post, while sobbing over today’s newspaper, but I’ve been silent because I don’t know where to begin, not because I have nothing to say, so I will begin here.

This post is written in response to the murder of six Canadian men in a Quebec mosque. It is written in response to Trump’s ban from the US on refugees and people born in seven countries with largely Islamic populations (perhaps temporary, but we shall see; extreme policies are often floated as temporary measures only to become slyly entrenched).

This post is also written in response to the outpouring of peaceful protest that began the day after Trump’s inauguration, less than two weeks ago, and continues today. I was fortunate enough to march in Toronto, in the women’s march, and although I was glad to share the moment with my sister, sister-in-law, and friends, I felt mostly sombre: I thought, this is just the start.

This morning, as soon as the house was emptied of kids, I began to weep, reading the stories of the men who were killed in Quebec City. Ordinary people who lived ordinary Canadian lives, and who believed in ordinary Canadian peace. The attack feels like a betrayal of Canada’s promise. We want to welcome refugees and immigrants. But bigots live here too, violence lives here too.

This morning, as soon as the house was emptied of kids, I began to weep, reading the stories of the men who were killed in Quebec City. Ordinary people who lived ordinary Canadian lives, and who believed in ordinary Canadian peace. The attack feels like a betrayal of Canada’s promise. We want to welcome refugees and immigrants. But bigots live here too, violence lives here too.

I am part of a neighbourhood group who has sponsored a refugee family from Syria; they arrived in December. I am fortunate enough to be quite closely involved in their lives here in Canada, helping with ESL, and also, I hope, offering my friendship. They are a beautiful young family, and their project is so enormous — moving to our cold country in winter, speaking no English, two small children, knowing no one — it sometimes overwhelms me to think about it. Yet they appear completely willing to embrace their new reality. I want them to thrive here.

I want Canada to be the promised land, where people thrive. But it isn’t always, is it.

Think about this land. The literal land over which I’m walking. There were people living on this land long before my ancestors (or a branch of my ancestors) settled here as farmers. These people were betrayed by the newcomers, by us, by Canada; not only was the land parcelled up and sold, but for almost a hundred years, residential schools tried to eradicate their cultures, to white-wash and convert and also to outright destroy, a history I learned nothing about in my Canadian education, a history running parallel to the stories we learned, obscured, buried. And this history isn’t past, it continues to inflect our present. When we invite newcomers to Canada, we can’t pretend this isn’t, also, our story: bigotry, violence, destruction, greed.

This might sound small, but I’ll tell you what guts me — the thought that my new friend, new to Canada, could be harassed for wearing her headscarf. I know this could happen — I know this does happen. It happens because of Othering.

I want Canada to be a place where Othering does not happen, where we don’t decide we know everything we need to know about a stranger based merely on how we’ve grouped him or her: according to race, class, gender, religion, sexual orientation, according to the flimsiest of superficial evidence, according to our own biases and blindness, according to our lack of imagination and empathy. I want Canada to be a place where strangers are welcomed because they have the opportunity to become known, for being themselves, complicated human selves.

Trump’s executive orders are Othering a huge swath of humanity: refugees, Mexicans, Muslims. Be afraid of these people, he is saying, they are not like us.

But they are. They are just like us. They are human. We are all human.

If we forget that, if we erase that, if we ignore that, we are doomed to division, to fear, to hatred, to war.

I am looking for hope. Hope seems to me something that you do, and by doing make real. So I’m looking for hope by spending a few mornings a week with a woman who was uprooted from her home by war, by designing and sharing curriculum that may inspire others to create, by coaching youth soccer, by walking and talking with friends, by getting up early to write, by marching, by making music, by meditating, by praying.

I keep looking for more ways to hope. Tell me yours, please.

xo, Carrie

Wednesday, Sep 7, 2016 | Big Thoughts, Confessions, Cooking, Family, Feminism, Friends, Spirit, Summer |

I didn’t do much more than hang out with these folks this summer. Now it is September 7th, and these folks are all in school, on their second day, which is much less exciting than a first day, for reasons we all understand. Never before have I felt so lonely in the house at this time of year. Maybe it’s because I was able to work effectively this summer even while the kids were home, so I don’t feel the same need to protect to my own space and quiet. Or maybe it’s because I need to develop some other social outlets. Our family was a remarkably self-sufficient unit this summer. It’s hard to get lonely or bored when potential companions and playmates can be found in the room next door.

I didn’t do much more than hang out with these folks this summer. Now it is September 7th, and these folks are all in school, on their second day, which is much less exciting than a first day, for reasons we all understand. Never before have I felt so lonely in the house at this time of year. Maybe it’s because I was able to work effectively this summer even while the kids were home, so I don’t feel the same need to protect to my own space and quiet. Or maybe it’s because I need to develop some other social outlets. Our family was a remarkably self-sufficient unit this summer. It’s hard to get lonely or bored when potential companions and playmates can be found in the room next door.

I write the best blog posts while I’m hanging out laundry. They’ve vanished by the time I sit down here.

I write the best blog posts while I’m hanging out laundry. They’ve vanished by the time I sit down here.

During our time at the cottage (five days of bliss), we brought little food, as we had been instructed to eat down the cupboards and freezer; we were the final guests this summer. This made meal planning a peculiarly satisfying challenge. The kids wanted to do the same thing here at home, so on Monday I did an inventory of our cupboards, freezers, pantry, and fridge that was astonishing and enlightening, and a little bit shaming. We are storing a lot of food that we’ve essentially forgotten exists. Yesterday, I took on the challenge and made a taboulleh salad out of quinoa, farro, kamut, all found, uncooked, in our fridge or freezer, chickpeas from the cupboard, a lemon and a half from the fridge, and olive oil. (I also bought parsley, cilantro, red onion, tomatoes and feta, so it wasn’t all from our supplies.) Two of four children were unhappy with the salad, but one of those two ate it anyway. “Does anyone actually like this?” said dissenting child # 1, and when everyone else said yes they did actually, dissenting child # 2 stayed silent and spooned the offending grains into his mouth while managing to look both angelic and patiently tormented.

During our time at the cottage (five days of bliss), we brought little food, as we had been instructed to eat down the cupboards and freezer; we were the final guests this summer. This made meal planning a peculiarly satisfying challenge. The kids wanted to do the same thing here at home, so on Monday I did an inventory of our cupboards, freezers, pantry, and fridge that was astonishing and enlightening, and a little bit shaming. We are storing a lot of food that we’ve essentially forgotten exists. Yesterday, I took on the challenge and made a taboulleh salad out of quinoa, farro, kamut, all found, uncooked, in our fridge or freezer, chickpeas from the cupboard, a lemon and a half from the fridge, and olive oil. (I also bought parsley, cilantro, red onion, tomatoes and feta, so it wasn’t all from our supplies.) Two of four children were unhappy with the salad, but one of those two ate it anyway. “Does anyone actually like this?” said dissenting child # 1, and when everyone else said yes they did actually, dissenting child # 2 stayed silent and spooned the offending grains into his mouth while managing to look both angelic and patiently tormented.

I like the idea of the cupboard challenge, but in practice it requires someone (i.e. me) to do a lot of planning and cooking from scratch. It is a challenge that will be challenged by our fall schedule. And by any non-domestic ambitions I may hold.

I like the idea of the cupboard challenge, but in practice it requires someone (i.e. me) to do a lot of planning and cooking from scratch. It is a challenge that will be challenged by our fall schedule. And by any non-domestic ambitions I may hold.

What are my non-domestic ambitions? I feel strangely removed from whatever it was I intended to do with my life. When a friend asked, on our morning run together, What are you looking forward to now? I had no reply.

What are my non-domestic ambitions? I feel strangely removed from whatever it was I intended to do with my life. When a friend asked, on our morning run together, What are you looking forward to now? I had no reply.

I have no reply. I’m just doing what’s before me (teaching, ferrying children, cooking challenges, possibly more soccer coaching, writing in some form or another), and I’ll do it to the best of my abilities. The good news is that I’m not not looking forward to anything either.

I have no reply. I’m just doing what’s before me (teaching, ferrying children, cooking challenges, possibly more soccer coaching, writing in some form or another), and I’ll do it to the best of my abilities. The good news is that I’m not not looking forward to anything either.

I’d forgotten how relaxed my mind had been all summer. It had so little extra to think about, to hold, to plan for, to juggle, to congregate onto a calendar. I mean, I appreciated that summer was wonderful and that my mind was relaxed. What I’d forgotten was how steep the decline in relaxation, in spaciousness, at this time of year. How does a person ever get anything done in this state? I seem dimly to recall the ability to parcel up time like the squares on a quilt, to do this and not that, or to do this while doing that. I dimly recall it, but I’m not looking forward to doing it; I guess that’s where I’m at on this the second day of the new school year.

I’d forgotten how relaxed my mind had been all summer. It had so little extra to think about, to hold, to plan for, to juggle, to congregate onto a calendar. I mean, I appreciated that summer was wonderful and that my mind was relaxed. What I’d forgotten was how steep the decline in relaxation, in spaciousness, at this time of year. How does a person ever get anything done in this state? I seem dimly to recall the ability to parcel up time like the squares on a quilt, to do this and not that, or to do this while doing that. I dimly recall it, but I’m not looking forward to doing it; I guess that’s where I’m at on this the second day of the new school year.

xo, Carrie

Sunday, Aug 14, 2016 | Feminism, Girl Runner, Good News, Running |

Silvia Ruegger running the homestretch of the women’s Olympic marathon in 1984. She competed for Canada in the first women’s marathon contested at the Olympics.

“I’m right there. Struggling. Fighting.”

Silvia Ruegger points to the young woman on her laptop’s open screen. She is running in film footage shot more than thirty years ago, in the heat of a historic race unfolding: the first women’s Olympic marathon, contested in Los Angeles, August 5, 1984. The light in the footage is blunt and bright, harsh against the pavement. The young woman from Canada has a muscular determined stride, her face streaming with sweat as she fights to stay even with the leaders.

It is a September evening in 2014, and I am in a Starbucks in Burlington, Ontario, with Silvia Ruegger, her laptop open on the table between us. We are watching Silvia’s childhood dream unfold.

A group of patrons nearby pretends not to be eavesdropping.

“The race was intense,” Silvia says. “Fifty women representing 33 nations. We all got bussed down to Santa Monica, ’cause it was a one-way course. And we were all in a gym. Everybody stretching, warming up, in one place. It was an interesting environment because it was almost like a celebration, because, I think, people knew that this was going to change everything. ’Cause sometimes people have to see something to believe it. They cannot believe it unless they see it. Right?”

On-screen, Silvia is hanging with the lead pack, her right shoulder dipping, a rugged rhythm to her pace.

“You don’t look …” I hesitate. I don’t want to sound critical.

“I don’t have finesse!” Silvia laughs. “And, actually, I never do! I’m blue-collar. That’s my style all the time. I just never had the finesse. Just blue-collar. Fighting it out.”

We watch the runners come into a water station and grab sponges to wet their already soaked heads. It’s chaos. At an earlier station, about 10 miles in, Silvia hit another runner who had stopped suddenly: “I ran”—she claps her hands together—“right into her. I went down. It was a wake-up call.” Silvia knew that she needed to pick it up, get out in the clear. And so she is running with the leaders, a handful of women and Silvia the least experienced, the youngest, twenty-three years old.

The footage skips ahead, and the women ascend a slight incline on an emptied stretch of Los Angeles highway, an eerie scene that looks apocalyptic: concrete girders, smooth grey pavement, an empty hot sky overhead, and gripping human effort. A male commentator’s voice breaks in to tell viewers that the race’s leader, American Joan Benoit, has an almost insurmountable lead. As if they hear him, the women leading the small pack—Rosa Mota of Portugal, Grete Waitz of Norway, Ingrid Kristiansen also of Norway—take off as one in a desperate attempt to reel Benoit back in. The young woman representing Canada, running the second marathon of her life, is dropped from the pack.

She isn’t wearing a watch. “I was not running for time,” Silvia tells me. “What would time be? I was running for place.” Her race strategy, planned with her coach, Hugh Cameron, could not be simpler: to stay with the leaders. To run with the best of the best. She knows it is her only chance at a medal.

“And all of a sudden, I was in no-man’s land. I couldn’t—I couldn’t even respond. I was running at my max.

“The first thought that crossed my mind was, ‘You’re slowing down! You started too fast. You’re in over your head!’

“So I entered the most difficult part of the race for me… The sun was oppressive. Emotional battle, physical battle, mental battle… My body was screaming, ‘Quit! Quit! Quit!’”

It is difficult to imagine the woman who sits across from me ever quitting. With three decades separating her from that race, Silvia Ruegger, now in her early 50s and a national director of a Christian children’s charity, radiates an almost impossible energy, drive, focus. How many times has she told this story? Yet she does not flag. She punctuates her sentences with bursts of physical enthusiasm, clapping her hands. She is very slender, almost fragile-looking, her dark hair cut in angular fashion, with bangs framing her face, her expression animated and intense.

“I call it a ‘Tunnel of Darkness’,” says Silvia. “And I’ll never forget seeing the light.” We’ve gone from metaphorical tunnel to literal tunnel, as the runners enter the stadium on the laptop’s screen and make their way once around the track.

Here is the winner, Joan Benoit, crossing the line, only 400 metres ahead of world-record-holder, Grete Waitz of Norway. We watch Grete Waitz finish second, and Rosa Mota of Portugal third.

And then we watch young Silvia enter the packed-to-the-rafters cheering stadium to complete the final 400 metres of her race, about four minutes behind the winner.

“What are you feeling?”

“Relief!”

The young Canadian crosses the finish line, slows to a walk. She’s placed 8th out of a field of 50 competitors, which remains the best showing by a Canadian in the women’s Olympic marathon, ever, and in a time of 2:29:09, fast enough to have won the men’s event at the Olympics during the first 40 years it was contested (the first men’s marathon of the modern Olympic Games was completed in just under three hours in 1896, in Rome).

On-screen, the footage ends.

I think about what Silvia told me before playing the video: “You don’t spend your life, and sacrifice, and give up those things just to be on the team. All of us go with the hope of being on that podium … to see your flag going up.” As remarkable as her accomplishment is, that young runner had never been going simply to be there. She had been going to win.

We’re quiet for a moment. Silvia shuts the laptop. The eavesdroppers retreat.

Here’s what I know: In a race several months after the Olympics, Silvia would set a Canadian marathon record that would stand until October, 2013. Could she have imagined that it would hold for so long? Silvia laughs with what sounds like astonishment: “I thought that I would reset the record. ’Cause I thought, when I ran 2:28, it was my third marathon, right? I had the Olympics, I had all my career, I was 23 years old, right?” Instead, only weeks after setting the Canadian record, Silvia would survive a near-fatal car-crash on a slippery winter road near Guelph, Ontario. Thrown from the vehicle. Severe concussion. Hematoma. Soft-tissue trauma. Two years of intense rehab. Yet she wouldn’t give up. She would spend the next twelve years trying and failing to make subsequent Olympic teams until her retirement in 1996. That was the last year, twenty years ago, that a Canadian woman ran in an Olympic marathon.

Until today.

Today, in Rio, August 14, 2016, Lanni Marchant, who only two days earlier competed for Canada in the 10,000 metres, finished 24th and Krista DuChene, the oldest competitor on Canada’s athletics team at age 39, finished 35th. It might be easy to dismiss their accomplishment, in the absence of medals, if you don’t know the history. But their presence in today’s race underscores both how difficult it has been to get there, and how tenacious you must be to make it happen.

Krista Duchene raises her arms in celebration as she crosses the finish line of the women’s marathon in Rio, 2016.

Every runner has a story. In Silvia’s, she is a teenager, running on a dark country concession near Newton, Ontario, before sun-up, in the depths of winter. Behind Silvia, her mom follows in the family’s station wagon, flooding Silvia’s path with light. As the sky shifts dimly to dawn, they approach a side road untouched by tire tracks, filled in from a recent snowfall, and Silvia waves to her mom: “I’m going down here. It hasn’t been ploughed. Meet me on the other side!”

Silvia’s mom, Ruth, rolls down her window. “Why are you putting yourself through this, Silvia? Is this really what you want to be doing?”

“Yeah, Mom,” says Silvia. “It’s gonna make me strong.” And the teenager in sneakers and mittens turns and bounds through the snowbanks.

Both Lanni and Krista have recorded marathon times faster than Silvia’s. They remain the only two Canadian women to do so.

As my interview with Silvia circles its end, I ask her: How has running changed you? And Silvia says, finally, coming around to the core of a thought amidst a gathering torrent of ideas: “I think in athletics, you go to the wall. And once you’ve done that, you can never go back. I’ve been ruined for—for the more. For the impossible. And I can never not live life that way.”

xo, Carrie

Note: I wrote several versions of this story in the months after Girl Runner was first published, pulling together months of research and interviews with Canadian women runners, some who competed before women were allowed to run long-distance events at the Olympics, including the marathon, and some who competed after. It’s a history that could have been bitterly told by those I interviewed, but never was. My only regret is that I failed to write the right story that would find its audience and celebrate these remarkable human beings. I’m choosing to publish this version here on my blog to celebrate the efforts of these women, and of everyone who has experienced the joy of running, no matter how fast. You have your story too.

Here. I present to you something that brings me joy every time I see it. [insert little arrow pointing up] You could call it a chore board, but that’s a rather pedestrian title given the magic it has created in our house this past week. Every morning, I write down chores that need doing, and the children sign up for them; the later you sleep, the less appealing your chore. Today, the last one out of bed got: “clean upstairs bathroom.” We’ve also banned video games or shows between the hours of 9am – 4pm. (Exception: older kids use their cellphones; I’m not great at monitoring this.) It’s still early days, but the chores are getting done with minimal fuss, perhaps because the assignment comes from the board, not from a nagging parent.

Here. I present to you something that brings me joy every time I see it. [insert little arrow pointing up] You could call it a chore board, but that’s a rather pedestrian title given the magic it has created in our house this past week. Every morning, I write down chores that need doing, and the children sign up for them; the later you sleep, the less appealing your chore. Today, the last one out of bed got: “clean upstairs bathroom.” We’ve also banned video games or shows between the hours of 9am – 4pm. (Exception: older kids use their cellphones; I’m not great at monitoring this.) It’s still early days, but the chores are getting done with minimal fuss, perhaps because the assignment comes from the board, not from a nagging parent. Other summer observations: I’m not waking up very early. This is the natural consequence of staying up too late! In addition to the kids running riot over regular bedtime hours, and soccer practices lasting (unofficially) till sundown, I’ve also been staying up late to watch feminist movies. Must explain. I’ve gotten myself, somewhat unofficially (?), onto the board of a locally run feminist film festival and my inbox is now full of films to view and consider. (Anyone out there with ideas for must-see recent feminist films, give me a shout!) But the only time I have to spare for movie-watching is rather late at night, post-soccer practice. Ergo, not waking up early. Ergo, early morning exercise-rate, somewhat reduced.

Other summer observations: I’m not waking up very early. This is the natural consequence of staying up too late! In addition to the kids running riot over regular bedtime hours, and soccer practices lasting (unofficially) till sundown, I’ve also been staying up late to watch feminist movies. Must explain. I’ve gotten myself, somewhat unofficially (?), onto the board of a locally run feminist film festival and my inbox is now full of films to view and consider. (Anyone out there with ideas for must-see recent feminist films, give me a shout!) But the only time I have to spare for movie-watching is rather late at night, post-soccer practice. Ergo, not waking up early. Ergo, early morning exercise-rate, somewhat reduced. Oh, I want to mention one more lovely addition to the routine: a shared journal with my eldest daughter. We write back and forth to each other, or draw back and forth, or quote poetry back and forth. I’ve devised a quick summarizing list that is easy to complete, if we’re writing late at night, when we’re too tired for originality. Filling out the list has become something I look forward to, every day. My answers are sometimes long and rambling, sometimes brief. (Want to try answering the list in the comments, below? I would love that.)

Oh, I want to mention one more lovely addition to the routine: a shared journal with my eldest daughter. We write back and forth to each other, or draw back and forth, or quote poetry back and forth. I’ve devised a quick summarizing list that is easy to complete, if we’re writing late at night, when we’re too tired for originality. Filling out the list has become something I look forward to, every day. My answers are sometimes long and rambling, sometimes brief. (Want to try answering the list in the comments, below? I would love that.)