Category: Art

Monday, Aug 21, 2017 | Adventure, Art, Big Thoughts, Lynda Barry, Peace, Politics, Spirit, Stand, Summer, Teaching, Work, Writing |

A person wonders whether she can carry home the things she learned, whether transformation in a radically different setting from home is sustainable. A person yearns to be the self she was while she was away. But a person knows, coming home is coming back to a crowd of needs waiting to be met. Even the house needs her. A person has so many loves. Loves are obligations but loves are also earned and cherished and what would a person write about were she to have no loves to tend to?

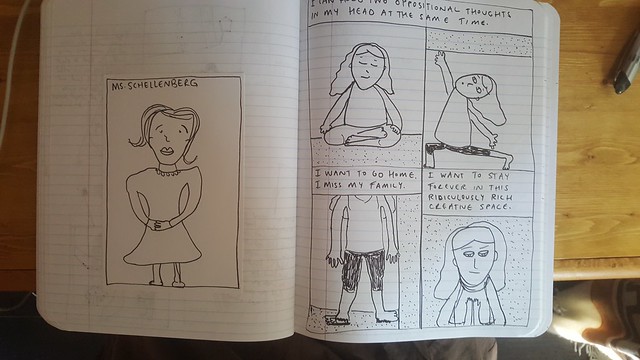

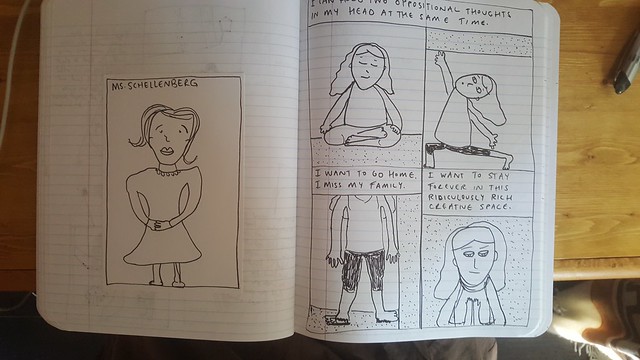

I can hold two oppositional thoughts in my head at the same time. I want to go home. I miss my family. I want to stay forever in this ridiculously rich creative space.

What I’m trying to say is that I’m home from Omega, in upstate New York, home from the Lynda Barry + Dan Chaon workshop, a 5-day intensive experience in a summer-camp-like setting, with an amazing yoga class every morning, ultra-healthy vegetarian/vegan food served three times daily, virtually no responsibilities, no chores, and perhaps most critically, almost no emotional labour except for the work that poured onto the page. My mind was uncluttered and immediately more open to images and connections. Will I be able to be joyful, I wondered on the evening we arrived, will my spirit find lightness? Is it still possible? I had my answer in less than a day: yes. It was so easy, under the circumstances, to be playful, attuned to what’s under the surface, easy to meet any challenge.

Writing isn’t easy, but it’s enjoyable, said Lynda Barry. She likened it to seeing runners go by in the middle of the day, and you can tell they’re enjoying it, but you never once think, hey, that looks easy. Writing — it’s the same. What this week kindled in me is a fire for the writing. For the possibility in writing, which is seductive to someone who entertains as rich a fantasy life as I do.

After Lynda Barry said goodbye, on the last morning, Dan Chaon, with whom she co-taught this workshop, helped us debrief our experience. Someone asked him about writing to an audience, and his answer had me in tears. It must have answered something very deep inside me, something neglected, lost, forgotten. I’m writing to my peers, he said. I’m writing to the writers I love, my kindred spirits.

I’m writing to my peers.

Am I capable of thinking of the writers I admire as peers? How does it change my mind and body to think: I am writing to Helen Oyeyemi. I am writing to Rumi. I am writing to Eden Robinson. I am writing to Ann Patchett, to Rilke, to Mavis Gallant, to Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, to Mary Oliver. Feelings of love and awe and excitement come over me. I am writing so my work will speak to their work. In Lynda Barry’s classroom, we show our drawings to each other, but we also show our drawing to each other’s drawings. It sounds flaky, but it’s a reminder: this work, once created, lives a life separate from our own.

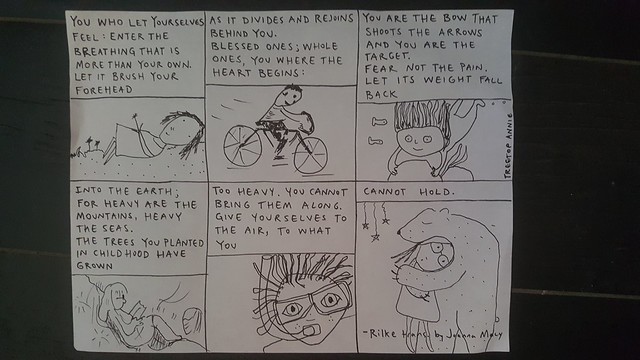

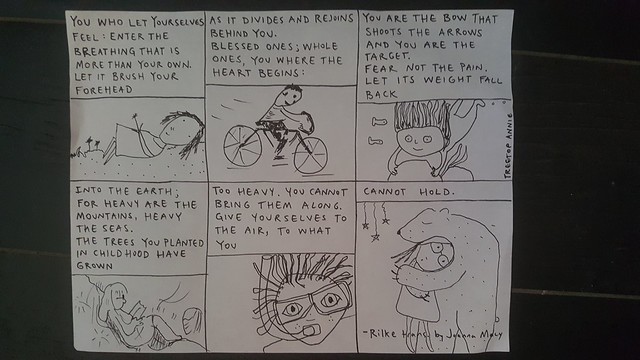

On Wednesday, I walked the labyrinth on campus, and spent a lot of time writing — my own writing, not guided writing. It was late in the evening. I decided to do one last project before snack and bed, something I’d been wanting to do for awhile: make the Rilke poem I’ve memorized and repeat often into a little cartoon. For the pictures, I looked at my peers’ attendance cards, hanging from the walls, and I chose images that seemed to speak to the words in the panel, and I copied them as best I could. All the drawings are drawings I admired, made by hands and minds I did not know. Then I taped the cartoon to the classroom wall and left it there for the rest of the week.

It was the kind of space that makes a person want to leave behind gifts. But on the last day, I untaped the cartoon from the wall and brought it home. It was the kind of space that makes a person want to believe she can bring what she found there home.

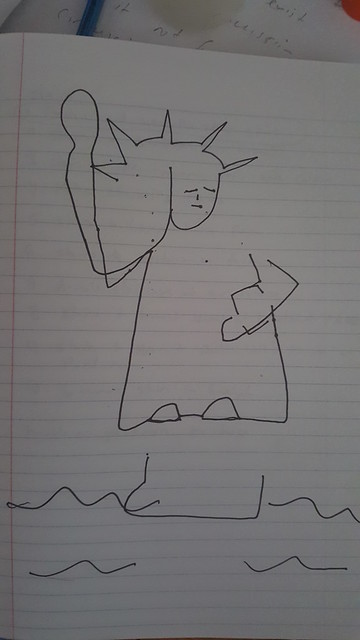

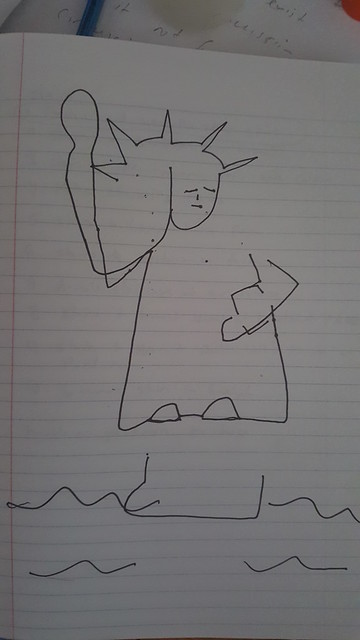

I know we were in another world, a bubble of creative vibes and chickpea scramble, but what was happening in the world was with us too, if at a remove. I mean, there we were in the United States of America during the week when the president spoke out in support of Nazis. There was pain and confusion in that classroom too. This feels like a crisis, said Lynda Barry, doesn’t it feel like a crisis? And everyone said yes. We are facing a crisis. What are we going to do about it? What are we going to do?

She didn’t have an answer. She just had us knuckle down and draw ourselves as a dejected Batman, draw the statue of Liberty with our eyes closed, make a map of a familiar walking path. And then she made us show our neighbour.

xo, Carrie aka Treetop Annie

Friday, Jul 14, 2017 | Art, Big Thoughts, Books, Confessions, Publishing, Reading, Spirit, Teaching, Work, Writing |

The longer I teach, the more I learn.

If I were to write a dissertation, now, my subject would be the short story. I would take a scalpel to the form, carve three-dimensional paper sculptures to show how beautifully various the short story can be. My focus, as a reader and a writer, has long been on Canadian literature, but the more widely I read, the more I wonder what Canadian literature stands for. Where are we right now? What are we lacking? Are we constrained by our Canadian-ness, because our patron is the state? Our violence is secretive and shameful. We don’t dare feast or riot. We would never burn the house down, and if we did, we’d make sure no one knew it was us. Also, outwardly, we appear reasonably satisfied with this state of affairs.

I could be wrong. I could be entirely very very wrong. Generalizations are almost certainly wrong, at least to some degree.

But here’s what I’ve learned, from teaching. For the past five years, I’ve assigned Canadian short stories for my students to read and discuss, and my students’ complaint has been consistent: why are these stories so similar? At first, I was baffled: the differences between the stories were so clear to me; subtle, perhaps, but clear. But as I’ve started to read and assign stories from international writers, some in translation, I’ve come to understand that my students were more perceptive than I. This is not to dismiss my beloved Canadian stories. But I see, now, that there is a world of stories out there that are different and not just in subtle ways, but in juicy, technically audacious ways: stories that are ugly, ungainly, colourful, lawless, unconventional, impolite, rowdy, hungry. Imperfect. Stories that dare to be disfigured, furiously cryptic, ridiculous, structurally untidy, fascinating, open, broken, big. Stories that can take the criticism, because they’re out there doing the dirty work, and they’ve got more important things to worry about.

The world is waiting to be read.

I can’t pretend to know what Canadian literature stands for, nor what it lacks, nor what it needs. I think we are in troubled waters, troubled times, but I’ve been devoted to CanLit for my whole life, steeped in the stuff, and this is my trouble, too. Times of transition are always troubled times. I believe this. Transition is what gets us somewhere new. Truth and reconciliation: painful. It’s painful to be wrong, but how much more painful is it to be a child of 12 for whom suicide is the answer to their pain, how much more painful to be this child’s family, community. This is our country, right now. This is Canada. And somehow, I think it’s our literature, too. Now is not the time to turn more inward, to hide away, to ignore, not listen, not try. It feels imperative — to try. To pay attention.

I want to write stories like the ones I’ve been reading from around the world, and I can try. I may not be able to, but others will. If I’m a very fortunate teacher, maybe my students will. Meanwhile, I can keep learning, listening and reading.

xo, Carrie

Friday, Jun 9, 2017 | Art, Big Thoughts, Confessions, Spirit, Stand, Word of the Year, Work, Writing |

I’m trying to write the draft of a new novel, but I’ll be honest with you—I feel no urgency to finish it. What I feel instead is a desire to keep it hidden away, like a secret treehouse where I can go to play and think, and where I feel safe. If I do finish it, it feels like that secret treehouse will vanish. Writing a novel requires time and solitude and there aren’t many moments available to sit and write, due to other things going on in my life; there aren’t many moments when my mind can rest, when I can trust that there won’t be an interruption. So I’m mostly writing at my office on campus, on days when I teach. I write by hand. I don’t seem to care whether the pieces match up, from day to day. I keep finding bits of the story written in random notebooks, forgotten. Who knows what these add up to? The story is a cocoon.

Just because I’ve published books, doesn’t mean publishing more is in my future.*

I’m strangely at peace with this. It is easy not to publish, after all. What would be impossible would be never to write again. I think that I will always write; whether that makes me a writer isn’t my business to decide. Right now, I am someone who tries to teach others how to write. It seems like a way to respond to the insularity and parochialism of Canadian literature—to nurture new voices, to make room for new stories.

The words from an Ann Patchett essay jump into my mind: “People like to ask me whether writing can be taught, and I say yes. I can teach you how to write a better sentence, how to write dialogue, maybe even how to construct a plot. But I can’t teach you how to have something to say.”

This seems to get at the essence of something that matters to me. I don’t want to publish unless I have something to say. Maybe it takes years to gather up something worth saying. Maybe it just does. Life has to be lived, experiences accrue, layer upon layer, and with time these turn into compost. A richness is turned over to feed new growth. I’m at a point in my writing life when I’ve got the skills I need. I know how to write a sentence, how to write dialogue, even how to construct a plot. Now I wait to see whether I have something to say; something worth sharing.

I am trying to memorize a poem, but it’s slow going. My mind can’t seem to hold the sequence of these words and images, maybe because my post-concussion brain is not the powerful instrument it once was (this is something I worry about, even though I tell myself not to worry). I would like to embed this poem into my being. Once you’ve memorized a poem, it becomes a part of you, it enters your cells. Lines of poetry flow from me at odd moments of the day, like mantras.

Part One, Sonnet IV

You who let yourselves feel: enter the breathing

that is more than your own.

Let it brush your forehead

as it divides and rejoins behind you.

Blessed ones, whole ones,

you where the heart begins:

You are the bow that shoots the arrows

and you are the target.

Fear not the pain. Let its weight fall back

into the earth;

For heavy are the mountains, heavy the seas.

The trees you planted in childhood have grown

too heavy. You cannot bring them along.

Give yourselves to the air, to what you cannot hold.

-Rilke, translated by Joanna Macy (with one small word change by me, because I didn’t like the original)

Whoa—I didn’t think I’d memorized it, but without referring to the text, I typed it out here, from beginning to end. I will check it over now to make sure everything is accurate, especially the line breaks and punctuation.

Hope is the thing with feathers / that perches in the soul, / and sings the tune without the words, / and never stops at all. -Emily Dickinson (I haven’t memorized all of this poem … but these are the words that popped into my head as I realized that I’d memorized Rilke, above.)

Hope is the thing with feathers. Hope is the thing with feathers.

This is not a bad time, or a sad time, I want to be clear—being at peace, escaping to my cocoon of fiction. I trust that if and when the season changes, I will recognize it. For now, I give myself to the air, to what I cannot hold.

xo, Carrie

*My kids’ picture book, Jammie Day, comes out this fall; but publishing a children’s book is not the same as publishing an adult book, for many reasons, which I won’t detail here; a discussion for another time.

Friday, Jun 2, 2017 | Art, Writing |

Poems should be written rarely and reluctantly,

under unbearable duress and only with the hope

that good spirits, not evil ones, choose us for their instrument.

-Czeslaw Milosz

Monday, May 8, 2017 | Art, Big Thoughts, Writing |

“I write in order to forget scorn, in order not to forget, in order not to hate, from hate, from love, from memory, and so as not to die. Writing is a luxury or, with luck, a rainbow of colours. It is my lifesaver when the water of the river or the sea tries to drag me under. When you want to die you fall in love with yourself, you look for something touching that will save you. …

“Writing is having a sprite within reach, something we can turn into a demon or a monster, but also something that will give us unexpected happiness or the wish to die. …

“The world is not magical. We make it magical all of a sudden inside us, and nobody finds out until many years later. But I did not hope to be known: that seemed the most horrible thing in the world to me. I will never know what I was hoping for. … What matters is what we write: that is what we are, not some puppet made up by those who talk and enclose us in a prison so different from our dreams. Will we always be students of ourselves?”

-Silvina Ocampo, Buenos Aires, 1987 (from the introduction to Thus Were Their Faces)

**

“Dante begins the Divine Comedy — which is both a poem and a record of the composition of that poem — with an account of finding himself in a dark, tangled wood, at night, having lost his way, after which the sun starts to rise. Virginia Woolf said that writing a novel is like walking through a dark room, holding a lantern which lights up what is already in the room anyway. Margaret Laurence and others have said that it is like Jacob wrestling with his angel in the night — an act in which wounding, naming, and blessing all take place at once.

“Obstruction, obscurity, emptiness, disorientation, twilight, blackout, often combined with a struggle or path or journey — an inability to see one’s way forward, but a feeling that there was a way forward, and that the act of going forward would eventually bring about the conditions for vision — these were the common elements in many descriptions of the process of writing. …

“Possibly, then, writing has to do with darkness, and a desire or perhaps a compulsion to enter it, and, with luck, to illuminate it, and to bring something back out to the light.”

-Margaret Atwood, 2002 (from the introduction to Negotiating with the Dead)

**

“If playing isn’t happiness or fun, if it is something which may lead to those things or to something else entirely, not being able to play is misery. No one stopped me from playing when I was alone, but there were times when I wasn’t able to, though I wanted to — there were times when nothing played back. Writers call it “writer’s block.” For kids there are other names for that feeling, though kids don’t usually know them.

“Fairy tales and myths are often about this very thing. They begin sometimes with this very situation: a dead kingdom. Its residents all turned to stone. It’s a good way to say it, that something alive is gone. …

“In a myth or a fairy tale, one doesn’t restore the kingdom by passivity, nor can it be done by force. It can’t be done by logic or thought. So how can it be done?

“Monsters and dangerous tasks seem to be part of it. Courage and terror and failure or what seems like failure, and then hopelessness and the approach of death convincingly. The happy ending is hardly important, though we may be glad it’s there. The real joy is knowing that if you felt the trouble in the story, your kingdom isn’t dead.”

-Lynda Barry, 2008 (from What It Is)

**

“When I think about writing, about going into a story, it is like I am travelling inside another world, as vivid and real as this world, and I am picking up clues, I am examining every detail up close or swooping high to see what the land looks like from above. I kneel and put my hands into the dirt and it is as if my hands are covered in earth. I am there and I am not here, so much, which is hard on those who wish me to remain here.

“When I think about going into a story, sometimes I feel like I am in a river and it is pulling me along, drawing me within its current. This is a state without fear, only wonder. I see shapes in the dark forest on either side, and the mystery is not where I’m going, the mystery is within the thick forest that surrounds me, impenetrable and beautiful, and it is my job to describe what I am seeing, even if I don’t fully understand it.”

-Carrie Snyder, 2017 (from this blog post, today, Monday, May 8, 4:27 pm)

Friday, May 5, 2017 | Adventure, Art, Big Thoughts, Creativity course, Drawing, Lynda Barry, Spirit, Teaching, Writing |

Six small, important takeaways from my winter creativity course…

Six small, important takeaways from my winter creativity course…

- Set a timer to get started. Give yourself tasks that can be completed in a set amount of time (7 minutes or 12 minutes or 30 minutes); or, give yourself a set amount of time in which to get started, then reassess when the timer goes (you will almost always want to add more time to the clock). Getting started is the hardest part. And you have to get started over and over, so you’d better figure out a way to trick yourself into beginning anew, repeatedly.

2. Don’t worry about making mistakes. In some of my favourite drawings, I made a big mistake early on but completed the drawing anyway. The mistake became an important part of the drawing, often creating depth that perfection couldn’t have; and making the mistake unconsciously freed me as I completed the work.

3. Mix it up. Even if your larger project is all text, and your expertise is writing, take time to draw if you’re feeling cramped or blocked. (Or sing or dance, etc.) Do/make/create something completely different, seemingly unrelated to what you’re working on. Remind yourself how fun it is just to make something.

4. Do the work even when you’re not feeling inspired. This goes back to item number one: just get started. You have an infinite capacity to surprise yourself.

5. Create routines that support your creativity. Perhaps more importantly, create routines that support your own mental health. Get outside. Meditate. Make time for friends. Volunteer. Help others. Share your enthusiasms. And when it’s time to do the work, do it. Don’t procrastinate. See item number one: set that timer and make something.

6. You can’t know what you’re making while you’re making it. “A writer is someone who, when faced with a blank page, knows absolutely nothing.” (to paraphrase Donald Barthelme) Remember this and be comforted, take heart. Your job is not to know what you’re making, or to explain what you’re doing, your job is to make something. See item number one.

xo, Carrie