Category: Big Thoughts

Sunday, Mar 18, 2018 | Big Thoughts, Dream, Organizing, Party, Sleep, Spirit |

Last night I dreamed I was being chased by a man with a gun. I ran and hid while he hunted me down.

I woke and all the hairs on my arms were standing on end. My mind was racing. I lay there in the dark, looking at the ceiling, trying to get the picture out of my mind—of a man with a gun, pointed at me. What I thought about, too, as I lay there, too awake and disturbed to sleep, was what it would be like to have experienced a situation like that for real, like the kids of Parkland. What a name. Parkland. Sounds like the name you’d give to a wholesome suburban community, though possibly a satirically wholesome suburban community. I thought about waking in the night to stare at the dark, mind racing, after being in lockdown in your classroom, after hearing gunshots in your school’s halls, after seeing someone shot and killed, after hiding, terrified, thinking you will die. And I thought, the March for Our Lives is not hyperbole for these kids. I thought, if someone with a gun has come into your school, you understand, in a way that others may not, how dire the situation is, how far gone, and you’d do anything, now, to prevent this happening to another kid, in another school.

I thought, this won’t end until enough people refuse to accept it as their reality.

I’m so glad I don’t live in the United States. It breaks my heart to say so, because I am a dual citizen, and because dear friends and family live in the States and love their country, and because there are so many good and wonderful things in the US. I grew up in the States. It was once my home. I remember when Canada seemed terribly foreign, even though my dad’s family had Canadian roots. Canada was cold and unknown, and I didn’t want to move here. I was ten. I’ve never moved back to the States. I’m almost wholly Canadian now. We have our own problems and even our own gun problem; but it doesn’t compare, nothing compares to the madness of the gun—the worship of the gun—in the United States of America. It’s almost as if guns are more sacred than life itself, in the USA. Certainly, the right to own and carry a gun is more protected than the right to be protected from gun violence. If the best answer politicians can come up with is more guns, arm the teachers, “harden” the schools into what amount to prisons—that’s not protection for the kids, that’s protection for the guns, again. Sell more guns.

I want to march. I want to go to Washington and march against the almighty gun.

The kids who are marching, the kids who’ve organized this, the brave outspoken truth-telling kids of Parkland feel like they’re living in a war zone. They’re living in a developed nation, a nation of enormous prosperity and wealth, yet they are not safe—they know they are not safe. They know this will happen again, and again, and again, in churches, in schools, in homes,on streets, and so they march. I hope they never give up hope. I hope they march and march and march for their lives until they change the course of history. I’d believed for so long that there was no changing this story—that mass shooting would follow mass shooting would follow mass shooting, with nothing but thoughts and prayers to comfort the survivors. But these Parkland kids, they give me hope. They’re changing the narrative. They’re digging in their heels.

I always thought the gun would win, because don’t people with guns always win?

But, no, they don’t. They don’t. Violence doesn’t always win. Power and bullying doesn’t always win. Money doesn’t always win. Oh, how I want to believe this.

Oh, how I love the kids from Parkland.

xo, Carrie

Wednesday, Feb 28, 2018 | Art, Big Thoughts, Confessions, Fire, Good News, Publishing, Writing |

I’ve got a new essay on mentorship up at TNQ, the local award-winning literary magazine that has accompanied me throughout my career: you’ll find all of the plot points in the essay, including publication, rejection and cause for hope. I hope you’ll read it.

xo, Carrie

Thursday, Feb 22, 2018 | Big Thoughts, Fire, Spirit, Stand, Work, Writing |

Earlier today I was writing, but then I had to stop writing because it was time to make a salad dressing, eat supper with my family, and clean up after supper. I was in a difficult part of the book, really struggling with it, and now I’m sitting down hours later, wondering how to find my way back in to that difficult spot? I feel a dull anger, but I don’t think it’s really to do with the interruption of thought, I suspect it’s a deeper frustration with my own inabilities to solve the problems in this book, which I fear I may not be clever enough or determined enough to do. The problem is that there is no big aha moment at the end of the book. There is no big reveal. No twist. The evil character remains evil. That’s another problem. The evil character is not an appealing and charismatic anti-hero who was once good and has fallen out of goodness, nor is he a polarizing or morally dubious character; no. All of his instincts and actions are reprehensible. Perhaps this points to a flaw in my imagination. I just can’t find his goodness, except possibly when he was a child. At the end of the book, has he changed? What’s revealed about him, ultimately?

So I sit here looking at the final page of this book, literally the final page, wondering where the redemption lies. Wondering whether this is a book about forgiveness or about revenge, or maybe it’s a book about being unable to forgive — and what happens then?

And then a few hours go by, and I’ve written a new ending that feels right, somehow, and the candle on my desk hasn’t burned out once this whole time. And now it’s bedtime. It’s getting late. I have a cartoon to finish and exercise early in the morning. It’s funny, and also comforting, to read what I wrote earlier in the evening. What I’ll probably remember about today is not the irritation or the frustration, which turned out to be momentary, fleeting, but the feeling of wholeness that arrived at the end of it all.

You have to withstand discomfort to make anything.

xo, Carrie

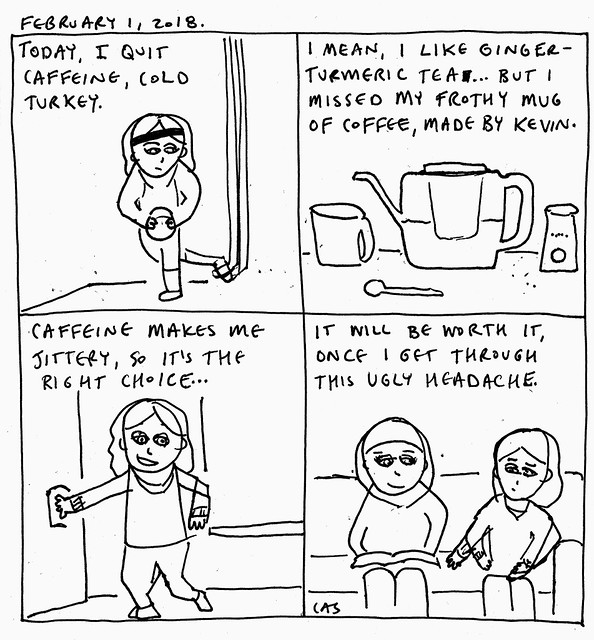

Friday, Feb 2, 2018 | Art, Big Thoughts, Blogging, Cartoons |

Today, I quit caffeine, cold turkey. I mean, I like ginger-turmeric tea … but this morning I missed my frothy mug of coffee, made by Kevin. Caffeine makes me jittery, so it’s the right choice. It will be worth it, once I get through this ugly headache.

I notice that I’m struggling with how to use this blog as a creative space, now that I’m focused on my cartooning project. I could post each cartoon here, daily, but I worry that my blog subscribers won’t want their inboxes inundated with daily posts. (Our inboxes are all full enough, right?)

Currently, I post the cartoons daily to Facebook and Twitter. (Although after a recent conversation with a good friend, also a writer, I’m considering quitting Twitter cold turkey, just like I’m quitting caffeine.)

I like publishing daily. The cartoons feel of the moment, and I enjoy sending them out in the world almost as soon as they’re made (I’ve given myself a buffer zone of one day, so yesterday’s cartoon gets published today).

I notice, too, that the cartoons are capable of holding a lot of thought, distilled into a few lines, and they seem to be taking the place of my blog, in terms of being a satisfying investment of creative energy, a comforting location for thinking out loud, for marking the moment. I just like making them. I like using this method to reflect on my day: by drawing scenes from it and distilling its meaning into a few sentences, a single theme or image. My journal pages are sloppy and untended, dumping grounds, piles that contain trash and beauty and who can tell which is which in all the mess? The cartoons are contained and coherent.

Life it not always coherent. The purpose of art is to give life shape, and meaning.

So making a cartoon feels strangely purposeful.

My question is: Should I be publishing my cartoons daily on this blog? I’m not sure. I suppose I could publish a cartoon and also write a blog post, should the desire overtake me…

Thinking out loud. Your thoughts?

xo, Carrie

Tuesday, Jan 16, 2018 | Adventure, Art, Big Thoughts, Cartoons, Death, Drawing, Fun, Lynda Barry, Play, Writing |

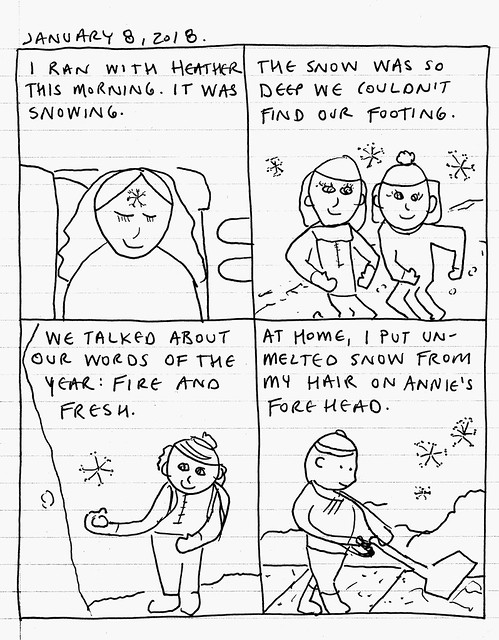

Title: Finding Footing

Captions: I ran with Heather this morning. It was snowing. The snow was so deep we couldn’t find our footing. We talked about our words of the year: fire and fresh. At home, I put unmelted snow from my hair on Annie’s forehead.

(What I like about this cartoon is the image of the snowflake that appears in each panel. It creates a visual motif that links the pictures with the text. The “on” should be “onto” but when writing in pen, mistakes get made and they’re permanent. So be it.)

The joy of embarking on a new project is the mystery of what its process will unearth. It’s too early into the cartooning project to guess what’s yet to be learned by doing it. What I’ve noticed so far is that already I have a sense of how many words can fit into each panel. Brevity and clarity are paramount. Thematic clarity is valuable, but sometimes a scattered cartoon, written and drawn in haste, can have its charms.

Title: Time-Challenged

Captions: This particular cartoon is very time-challenged. Things that happened today: Forgot to pick up Angus from work … Tuned out during scripture reading at church … Walked backward into the cold wind with Calvin.

(This cartoon was written and drawn in almost exactly 10 minutes, which I think is the absolute minimum amount of time required.)

Some days I’ve drawn two cartoons, one on a political subject, and the other more personal. For the purposes of keeping the project streamlined, I’m allowing myself to post only one cartoon each day (on Facebook and Twitter); so far, I’ve chosen the personal over the political. The political cartoons have gone into blog posts instead. I don’t feel that I’ve settled on a drawing singular style, yet. I like that. I like the freedom to experiment with both subject matter and style.

Title: Is It Like Climbing A Mountain Of Snow?

Captions: What happens if I don’t feel like drawing? Is it like climbing a mountain of snow to get to campus? Like doing the dishes and vacuuming? If I just show up, just do it, just keep going, it will happen?

(This was the one day so far that I really didn’t feel like cartooning. I’m glad that I did. It’s a good reminder to just show up and do it, even if you don’t feel like it; good advice for life in general, for writing in particular.)

Questions I’m mulling: What makes a good cartoon? What’s too personal, in terms of subject matter? Would these cartoons be of interest only to family and friends? Is it possible to find the universal in the daily? (Of course it is! The question, really, is how?)

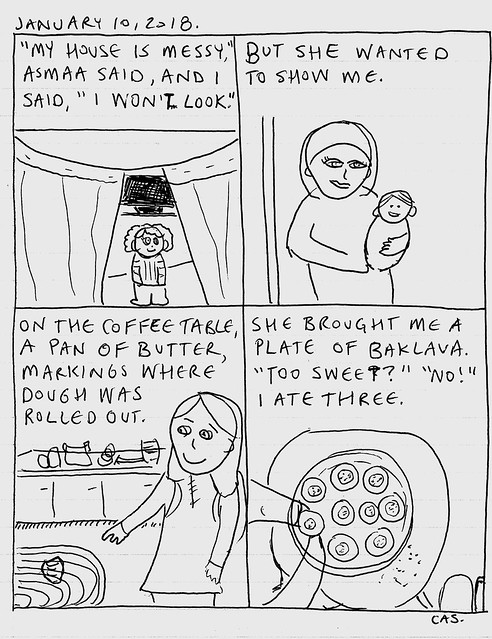

Title: Messy House

Caption: “My house is messy,” Asmaa said, and I said, “I won’t look.” But she wanted to show me. On the coffee table, a pan of butter, markings where dough was rolled out. She brought me a plate of baklava. “Too sweet?” “No!” I ate three.

(Most of these cartoons pair random scenes from the day with largely unrelated captions, and I enjoy discovering how these two dissimilar things respond to each other, but for this one, all the scenes drawn come from the story described in the text.)

Something interesting I’ve observed: that cartoons have the capacity to envelope sad, difficult narratives in a way that eases the pain, I think. Something I think about quite a lot is how to write about trauma without traumatizing the reader. I see in cartooning a possible means of tackling challenging subjects in non-traumatizing ways. Cartoons remind me of poems, a bit.

Title: This Day

Captions: This day has almost crushed me, yet it hasn’t been hard, objectively. I felt close to collapse, inside and out. I felt swarmed inside by anxiety that was almost pain. Yet, I did all of the things.

(Here, I think the scenes from the day soften the description of depression/anxiety in the text.)

Things I like about this project: I get to draw everyday. It’s an opportunity to reflect on my day, and pay attention to it in a different, unusual, creative way. It’s also an opportunity to invent thematic coherence and narrative out of the raw material of life. Life is raw. We humans, we have a tendency to pattern. Pattern may be illusion, but it is powerful. Pattern brings comfort — order to disorder, shape to chaos, coherence to uncertainty.

Title: Suddenly I Felt That I Understood

Captions: Today, I baked bread and I read Mary Oliver’s A Poetry Handbook. In it, she quotes a line from Emily Dickinson… “After great pain, a formal feeling comes —” Which suddenly I felt that I understood absolutely.

(The drawing of my hands kneading bread dough didn’t really turn out. But now you know what that panel is all about. Kind of looks like two islands separating in the middle of a lake … or, I don’t know; what do you see? I’m trying very hard not to re-do any “mistakes” in the cartoons, but rather to accept them as speaking from or to some secret part of myself I couldn’t otherwise reveal.)

xo, Carrie

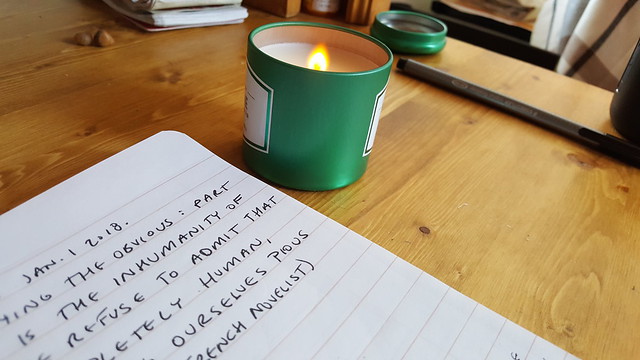

Monday, Jan 8, 2018 | Art, Big Thoughts, Fire, Meditation, Peace, Spirit, Word of the Year |

New ritual: I begin my desk-time by lighting a candle. The expectant flare of the match and comforting flickering flame marks a small opening moment to help me begin. The candle, which I almost felt ashamed of purchasing (impulse buy; no reason why; it was on sale), is suddenly useful, a tiny reminder of the word I’ve chosen to meditate on for this year: perhaps as a guide, perhaps as warning. Even the tiny flame of a single candle is mesmerizing, its movements mysterious, its light enticing.

FIRE.

The word fire initially drew my attention because I was thinking of creative fire, of passion, of burning brightly in pursuit of art. Which sounds howlingly pretentious, I realize. But I felt comforted by the image that accompanied the word: of a furnace, deep inside, glowing with steady bright heat.

Fire is dangerous, as elements are. I pictured, too, a fire that burns across a prairie, leaving behind blackened space, but also a place for new growth in fertile soil — not a wasteland, after all.

Fire is sacred, precious, life and death. Without it, we would be hungry and cold in the dark.

A fire either is, or is not. When I blow out this candle, its flame vanishes. What keeps a fire alive? It needs oxygen to burn, and energy. It devours fuel. Some fuel burns bright and quick, while other fuel burns slow and steady. But in time, all fuel will run out and must be replenished.

You can’t leave a fire untended. It will burn out, or burn out of control. Either way, it needs attention.

What fires am I tending now? What feeds my fire?

I think of the story of the Little Match Girl, which I adored as a child of melodramatic bent. How the brief flame of each lit match gave the girl temporary comfort and relief — and visions of warmth and plenty — even while she froze to death, shoeless, in the street. Fire as illusion of heat.

Fire as passion, fire as creative, fire as necessary; fire as destructive, fire as hungry, fire as all-consuming, insatiable.

I fear this word and yet it draws me. What would happen if I let my fire burn? What does that even mean? Do I know?

One last image that keeps coming around: Edna St. Vincent Millay’s poem “First Fig.”

My candle burns at both ends;

It will not last the night.

But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends —

It gives a lovely light!

xo, Carrie

PS The cartooning project continues, day by day. I’m posting a daily cartoon on Twitter and Facebook, and plan to use some here too, in future posts.